(English version below)

El abril de 2020 fue el mes dramático en el que el Covid 19 irrumpió en el Reino Unido. Hizo estragos e infundió pánico a la ciudadanía.

Desde ese momento en adelante la enfermedad empezó por la senda de declive. Ahora, cinco meses después de su erupción, la infección languidece en la lenta manera típica de cualquier epidemia, desapareciendo a la derecha del gráfico como una línea cada vez más plana.

A pesar de esto, no hay ningún sentido de alivio generalizado. Más bien, hay una reacción paradójica.

Cuanto más baja la tasa diaria de muertes*,

Cuanto más se desciende la cifra de gente ingresada*,

Cuanto más se reduce la cantidad de los pacientes que requieren ventilación mecánica*,

…….más se incrementa la histeria.

Acabamos de volver, un amigo y yo, de una semana en Cornualles, un condado atlántico que se parece un poco a Galicia. No hay mucha industria por ahí y es un lugar que depende del turismo. Hasta hace poco el turismo se quedó suspendido a causa del virus. Antes de que se levantara la suspensión las advertencias gubernamentales dieron un susto de muerte a la gente local y las cámaras de comercio de la comarca: Iban a punto de recibir una invasión de zombis.

El primer día de nuestras vacaciones decidimos dar un paseo a la playa. Estaba comenzando a llover y decidimos echar el atajo que nos llevaba por un prado. Notamos que una pareja de ancianos estaba observándonos desde una colina en medio del campo que atravesábamos. Antes de que llegamos a su altura ellos se alejaron exageradamente del sendero, apartándose varios metros de nosotros. La señora se dirigió a nosotros en un tono sarcástico:

“¿Llevan con ustedes el gel antiséptico que necesitarán para limpiar sus manos antes de que agarren la verja?” Pues, yo no esperaba tanta hostilidad y su brusquedad me dejó estupefacto Y no sabía cómo responder. Decidimos fingir que no habíamos oído sus palabras y pasamos de largo.

En el pequeño pueblo en que habíamos alquilado un apartamento el temor de contagio estaba muy, muy alto. No estábamos permitido tomar café en la cafetería. Teníamos que pedir un café para llevar, y lo hacíamos a la puerta del local, solicitándolo por una ranura de buzón que habían cortado en el centro de una gruesa lámina de plástico que cubría la puerta. Al otro lado de la lámina protectora estaba una mujer que llevaba delantal, mascarilla y guantes desechables. Un segundo empleado, que iba ataviado de manera similar, entregó el café dejándolo en otra ventanilla de dimensiones parecidas a las de la primera, la única diferencia siendo que esta vez la ranura estaba orientada verticalmente.

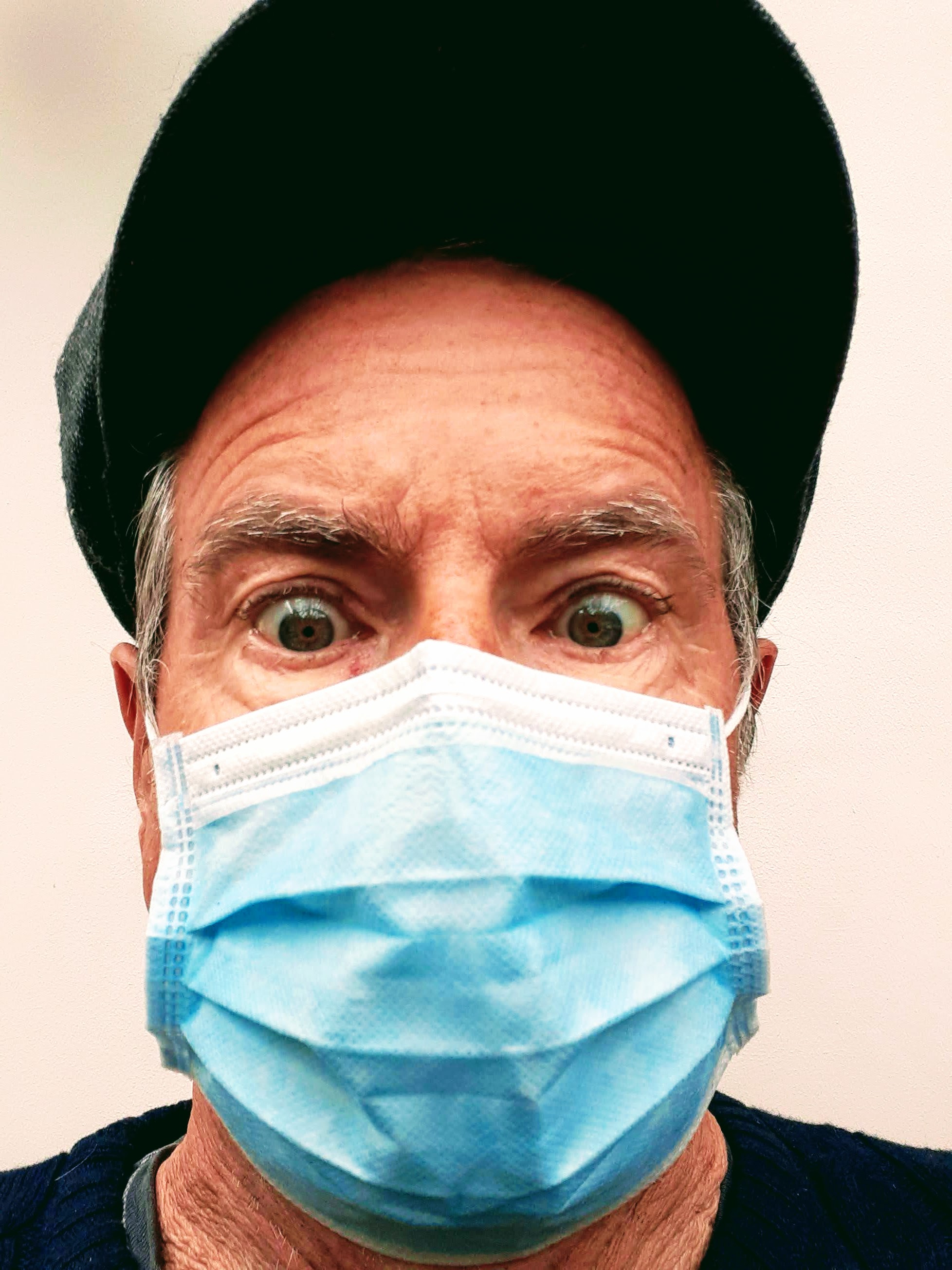

Muchas personas siguen muy preocupadas y desconfían de la gente con la que se cruzan en la calle. Andan con cara de pocos amigos. Cambian de acera para no tener que hablar con sus vecinos. Se muestran agresivas cuando creen que otros no mantienen la distancia. Hay mucha gente que nunca se quita la mascarilla por los riesgos de contaminación, hasta cuando conducen con las ventanillas cerradas; se parapetan detrás del volante, sus ojos revelando una mezcla de resentimiento, inquietud y paranoia; parecen estar en fuga.

Estoy preocupado por la salud mental de los ingleses. Alguien describió el carácter inglés como “cortés pero hostil”. La descripción tiene un fondo de verdad. Nuestro carácter ya es receloso, reservado y distante. ¿Cuáles serían las consecuencias para nosotros si pasáramos un período prolongado en el que nos acostumbráramos a rechazar todo contacto con los demás? ¿Nos volveríamos aún más xenófobos, aún más renuentes a participar con otras naciones y aún más aislados personal y nacionalmente?

Según muchos expertos (si hay expertos en esta pandemia) parece posible que nunca vamos a eliminar el virus por completo. Puede que la línea del gráfico jamás sea plana del todo.

En el comienzo, el virus causó un elevado número de víctimas mortales entre el personal médico y enfermero y entre otros trabajadores (por ejemplo, conductores de autobuses), gente que tuvo una exposición prolongada a la infección. También, afectó desmesuradamente a los obesos, los enfermos crónicos y los que tuvieron el sistema inmunitario debilitado. Y por supuesto, impactó mal en la gente desfavorecida de este país, la gente que lleva una vida más precaria, más hacinada, peor nutrida y con menos acceso a la atención médica.

Recientemente el número de personas positivas está en alza. Pero, a la vez el número de pruebas ha proliferado. Y esto puede tener algo que ver con la subida de la tasa de detección. Por fortuna, las muertes, los pacientes ingresados y los que necesitan ventilación asistida siguen a la baja.

Con el número de personas que ya han tenido el virus, los que lo han contraído recientemente y los que todavía no lo hayan padecido pero que hacen cola sin saberlo, parece que por fin nos estamos acercando a una solución: vamos derivando, de manera lenta pero segura, hacia una inmunidad colectiva. Y si esta no se produce pronto, los asesores gubernamentales nos aseguran que hay en camino una campaña de vacunación.

Por supuesto van a producirse rebrotes. Además, los virus mutan cuando quieran. Sin embargo, en un futuro no demasiado lejos, el Covid 19 y sus derivaciones pasarán a ser nada más que nuevos miembros de la pandilla de enfermedades seudogripales que acechan a los debilitados que ya no puedan resistir; a los ya afligidos de otras enfermedades terminales; a los que se acerquen al final de sus días. El Covid se convertirá en un ejemplo más de las muchas enfermedades letales que se emboscan para sorprendernos con la dosis letal. Ya no será la peste mortífera que la creíamos en su cenit, la plaga bubónica que amenazaba con diezmar la población del mundo, sino otro disfraz que lleve la parca cuando nos abofetee en el último momento con el golpe de gracia.

Tenemos que morir de algo. Entonces, a un punto indeterminado en el futuro, tendremos que aceptar el virus, aprender a bajar la guardia y seguir con nuestras vidas.

Ojalá decidamos hacerlo más pronto que tarde. Ojalá se acabe nuestra pusilanimidad cuanto antes.

Deberíamos recordar las palabras de Franklin Roosevelt en su discurso en la ocasión de su inauguración como presidente de EEUU en 1933, otro año de crisis global; una crisis causada no por una pandemia sino por la Gran Depresión;

“Por tanto, ante todo, permítanme asegurarles mi firme convicción de que a lo único que debemos temer es al temor mismo, a un terror indescriptible, sin causa ni justificación, que esta paralizando los esfuerzos necesarios para convertir el retroceso en progreso.”

* https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/

Covid 19: The only thing that we have to fear is fear itself

April 2020 was the dramatic month in which Covid 19 burst upon the United Kingdom. It caused havoc and spread panic amongst the population.

From that time onwards the illness began its downward path. Now, five months after its eruption the infection languishes in the gradual way of all viruses, slowly flatlining to the right of the graph.

Despite this, there is no generalised sense of relief. Rather, there is a paradoxical reaction.

The more that the daily death rate declines*,

The more that the number of people in hospital goes down*,

The less patients who require mechanical ventilation*,

……the more the hysteria rises.

A friend and I have just returned from a week in Cornwall, an Atlantic county which somewhat resembles Galicia. There isn’t much industry around there and it’s a place that depends upon tourism. Until very recently tourism was suspended because of the virus. Before the suspension was lifted, government warnings put the fear of God into the local people and the chambers of commerce of the region: they were about to receive an invasion of zombies.

The first day of our holiday we decided to walk to the beach. It was beginning to rain and we decided to take the short cut across a field. We noted that an elderly couple were observing us from a rise in the centre of the field that we were crossing. Before we reached their viewpoint they moved away exaggeratedly from the footpath, distancing themselves several metres from ourselves. The lady addressed us in a sarcastic tone:

“Do you have the antiseptic gel with you that you will need to clean your hands before you open the gate?” Well, I wasn’t expecting such hostility and I was struck dumb by her rudeness. I didn’t know what to say. We decided to pretend we hadn’t heard and walked on.

In the small town in which we had rented an apartment the fear of contagion was high, very high. We were not allowed to drink coffee in the café. We had to order one to take away, and we did so at the door of the establishment, asking for it through letter box that they had cut in the middle of a thick sheet of plastic covering the doorway. On the other side of the protective screen stood a woman wearing an apron, a mask and disposable gloves. A second employee, who was got up in the same way, delivered the coffee, leaving it in another little opening of a similar size as the first, the only difference being that this time it was oriented vertically.

Many people continue to be very worried and mistrust others they meet in the street. They look friendless. They switch pavements to avoid talking to their neighbours. They become aggressive when they think others are not keeping the right distance. To avoid the risk of contamination, many people never take off their masks, even when they are driving with the windows up; they barricade themselves behind the steering wheel, their eyes revealing a mixture of resentment, disquiet and paranoia; they look as if they are on the run.

I am concerned for the mental health of the English. Someone described the English character as “polite yet hostile”. The description contains some truth. Our character is reluctant, reserved and distant. What would be the consequences for us if we were to spend a prolonged period during which we became accustomed to reject all contact with others? Would we become even more xenophobic, even more reluctant to participate with other nations and become even more isolated personally and nationally?

According to many experts (if there are experts on this pandemic) it seems possible that we will never totally eliminate the virus. It might be that the graph never truly flatlines.

In the beginning, the virus caused great loss of life amongst medical and nursing staff as well as other workers (such as bus drivers, for example), people who had had prolonged exposure to the infection. Also, it affected disproportionately the obese, the chronically ill and those with a suppressed immune system. And, of course, it impacted badly on the underprivileged of this country, the impoverished, the overcrowded, the badly-fed and those who have less access to medical treatment.

Recently the number of people who have tested positive has been on the rise. But, at the same time, there has been a proliferation of testing and this might have something to do with a rise in the rate of detection. Fortunately, the numbers of deaths, patients in hospital and those on assisted ventilation continue to go down.

With the number of people who have had the virus, those who have contracted it recently and those who haven’t suffered it yet but who are unknowingly in the queue, it seems we are nearing a solution: we are drifting, slowly but surely, towards a herd immunity. And if this doesn’t come soon, government advisors assure us that a programme of vaccination is on the way.

Of course, there will be new outbreaks. Besides, viruses mutate when they feel like it. However, in the not too distant future, Covid 19 and its variants will become no more than fresh members of the gang of flu-like diseases that lie in wait for those who are too weak to resist; those who are already suffering from terminal illness; those who are nearing the end of their lives. Covid will become just another one of the many illnesses that leap out and surprise us at the last minute with a lethal dose. It will no longer be the deadly disease we believed it to be at its height, the bubonic plague that threatened to decimate the population of the World, but simply another get-up worn by the Grim Reaper when he cuffs us with the coup de grâce.

We have to die of something. So, at some time in the future, we will have to accept the virus, learn to lower our guard and get on with our lives.

Let’s hope we decide to do it sooner rather than later. Let’s hope our faintheartedness comes to an end as soon as possible.

We should remember the words of Franklin Roosevelt on the occasion of his inauguration as President of the United states in 1933, another year of global crisis; a crisis not caused by a pandemic but by the Great Depression:

“So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself, nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”