How Mrs Thatcher viewed the world

I remember sitting in one of the cubicles in the toilets at Sussex University in 1972 and seeing graffiti that someone had scribbled just above the toilet roll holder: “Degrees in Sociology. Please take one”.

Thus it was that this anonymous wag, surely a serious student of one of the traditional sciences or perhaps a spokesperson for one of the more venerable humanities, showed their disdain for this new pseudo-academic abomination that some progressives had fertilised in a laboratory test tube in the USA: an unholy foetus that they had then implanted in the womb of the mother of university courses so that she might carry it to term; an unnatural child of the godless union of science and the arts; most certainly a weak two-headed monster that would soon die, being organically and intellectually nonviable.

A scientific study of society? Bah!

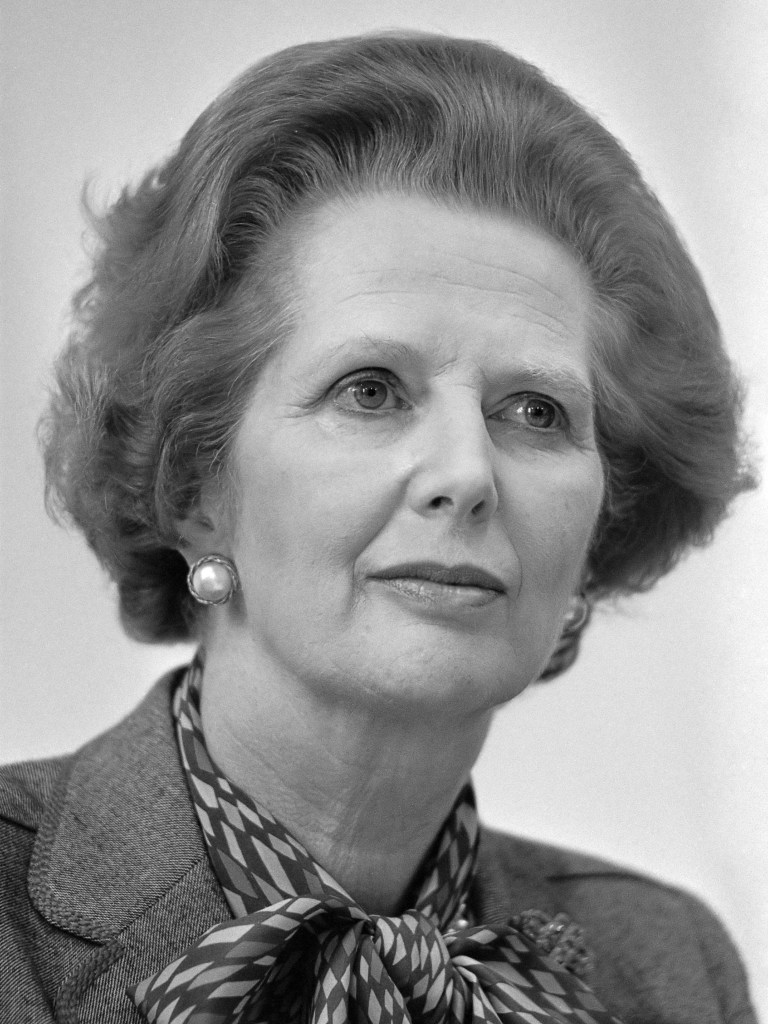

Even Mrs Thatcher, Prime Minister between 1979 and 1990, was outraged. Society, society? ‘There is no such thing,’ quoted the women’s magazine Woman’s Own from an interview with her published in 1979.

Just as sociology was a fraudulent subject, socialism was an aberrant, illusory and ill-conceived belief: a fairy tale that sought to give rights to people who did not deserve them. The myth of socialism had to be debunked and the misguided structures erected by its confused proponents had to be abolished.

She was doctrinally opposed to all the social measures that had been carried out previously by Labour governments. She made it her mission to ruthlessly cut out all regulatory framework that inhibited the effort of the individual. She believed that if we achieve something in life, our success should be due exclusively to our own personal endeavour.

Margaret Thatcher had the air of a preacher. Within the Conservative Party, she was considered a renovating spirit: an evangelist and idealist who preached a return to traditional values. She proclaimed a nineteenth-century Conservative message. She was a tremendously determined force of nature. She was scary. (She was curiously very popular with the Russian public.) She inspired every Conservative government that followed her to continue with the main task of privatising every industry and public service that had previously been nationalised by Labour.

She was almost single-handedly responsible for the resurgence of the Conservative Party at the end of the twentieth century. She was the instigator of the wave of denationalisation that began in the 1980s, the subsequent privatisation of all public transport, and the weakening and decline of trade union power (see the struggle between her and Arthur Scargill, the leader of the National Union of Mineworkers). She gave free rein to the deregulation of utilities. The electricity, gas and water monopolies were smashed to pieces. In their place appeared a jungle of small electricity, water and gas supply companies.

These new small-fiefdom utilities returned to a true free market economy, supplying not only electricity, gas and water but also chaos, inefficiency and large dividends for its shareholders. Today, our rivers are more shit than water. Oh, and think carefully before you travel on the jigsaw of 28 companies that now run on our national rail network. The delays and cancellations are worse than ever.

Another “abomination” that bothered Mrs Thatcher was council housing

Since the end of the First World War, we have had a system of social housing built by local governments in Britain. This system has its roots in the First World War. During the war, the poor physical condition of many urban recruits to the army was noted with alarm. The day after the armistice in November 1918, the then Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, promised a new programme to improve the health of the general population, a programme that included a new social housing system. From that date onwards, every local council in the country would be responsible for building decent homes for the heroes who had won the war. Lloyd George emphasised that the country owed a special debt of gratitude to the rank-and-file soldiers, the members of the working class who made victory possible. They would rent their new homes at an affordable price, subsidised by the government. From that time on, people who did not earn enough money to afford to buy their own home could live in good quality accommodation with security of tenure, courtesy of the state.

Thus, a good social housing system was created. It suffered some ups and downs due to the Second World War, but, generally speaking, it worked well and served the British working class well…….

………until Mrs Thatcher came to power and decided that council tenants should have the right to buy the social housing in which they lived.

Her new law of 1980 stated that local councils had to offer to sell their houses to any tenants who had lived in them for the necessary number of years to become eligible to buy at a greatly reduced price. Although they had built the homes with their own funds, local governments were not allowed to keep the money from the sale. They were forced to give it all to central government. That is why all local councils, regardless of their political affiliation, immediately stopped building council houses.

Thatcher’s policy had several objectives, mainly the inclusion of the working class in the «property-owning democracy», an emotive phrase always on the tip of the tongue of every true member of the Conservative Party. Amongst the party faithful, it was considered that this key policy would allow the Tories to ingratiate themselves with the “upper working class” and thereby encourage them to vote Conservative.

In the long term, the intention was to minimise, if not entirely eliminate, the public housing stock.

As a result of the right-to-buy programme, the number of these homes has fallen dramatically. According to the government’s own figures, in England alone between 1980 and 2024, the country lost around 2,020,279 social housing units.

This loss has had very bad consequences for local governments and has directly led to private landlords lining their pockets with public money.

Who owns these social housing units now?

As you might expect, a substantial proportion of the new owners are the people for whom the policy was intended. However, in 2013, The Daily Mirror newspaper published an analysis of the other new owners who had also acquired a significant number of former council dwellings.

‘A third of the council homes sold in the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher are now owned by private landlords. In one London borough, almost half of social housing is sublet to tenants.’

Often, these new owners were not individuals but offshore companies, and the social housing they now own is part of their property investment portfolios.

The situation is deteriorating. According to the New Economics Foundation, by 2024, 41% of former social housing, previously owned by local councils, was being rented at market rates, a figure hundreds of percent higher than that which the tenants previously paid to the local authority.

How are former council homes acquired?

As with any house, there comes a time when former council houses are sold. Sometimes, owners leave them as inheritance when they die. Many heirs sell them to divide the proceeds among themselves; other couples divorce and sell their house; not all new buyers want to continue living there happily ever after, some simply sell because they have bought their house at a very reasonable price from the council and want to make a quick profit. But whatever the reason for the sale, the downside of selling an ex-council house is that they do not fly off the shelf to ordinary buyers.

Houses like these tend to attract mortgages of considerably less than 100%. They have problems which do not inspire building societies with confidence. They often have issues with construction and repairs as council flats are inevitably located within blocks of council accommodation. In the case of the latter, they share a roof, or in a worst case scenario, they have inflammable cladding (as was the notorious case of Grenfell Tower in the North Kensington neighbourhood of West London where, in 2017, 72 people died in a fire which spread rapidly and there was no proper procedure for evacuation nor any easy escape.)

Furthermore, the ordinary people who consider buying an old municipal flat are usually those with less purchasing power and who often have additional problems that prevent them from obtaining a mortgage, e.g. they do not have the cash flow to pay between 1% and 2% of the sale price in estate agent fees. In addition, if they are not first-time buyers, they will be required to pay a 5% stamp duty on the price band of homes between £250,000 and £925,000 (the typical price band across the UK).

‘What you need is a fast buyer’

A fast buyer is a company (or, in rare cases, an individual) that has the money up front to buy the flat or house. Listen to how LDN Properties describes its work as a fast buyer on its website. Listen to the siren song, the comforting voice of the fairy godmother, the promise of easy money:

» These companies are able to make speedy and competitive offers for buying a large range of freehold and leasehold flats and houses, no matter their shape, age, condition or size. They are called fast buyers because they can generally complete the process of purchasing your home in a few short weeks, and that includes exchanging contracts and all other steps.»

There are many of these financial conglomerates that have no cash flow problems and have a lot of capital available instantly. They buy at ridiculously low prices.

» A clear benefit of using a fast buyer is that they do not discriminate when purchasing homes and can consider almost any type of property that might struggle to sell using other methods, such as ex-council flats, inherited but unwanted retirement houses, properties situated on noisy streets, houses of multiple occupancy, flats with cladding, homes with septic tanks, and more.»

What’s more, you don’t have to pay anything to an estate agent.

There have been many scandalous cases involving people at the heart of the Conservative Party. For example, tycoon Charles Gow and his wife own at least 40 social housing properties on a south London estate. Charles Gow’s father was Ian Gow, one of Margaret Thatcher’s top aides and the housing minister during the early years of the right to buy.

No law has been broken by buying social housing in this way. It’s just that the public money that was used to build these houses has now become a gold mine for a man who doesn’t need them, neither for his own family nor for the accommodation of his charming personal collection of working class people.

The consequences for local councils and the Chancellor of the Exchequer (and, ultimately, the rest of us)

In Great Britain since 1948, local governments have been responsible for providing temporary accommodation to all vulnerable homeless families and individuals. The erosion of their own housing stock has made this task increasingly difficult and costly. For example, in London alone, the capital’s 32 boroughs pay a total of £4 million per day to private landlords to fulfil their duty to provide shelter for the homeless. Ironically, in order to fulfil this responsibility, local councils are often forced to rent a former council property, a house that they themselves owned in the past: one that now costs them an exorbitant rent. In other words, not only have local authorities lost housing, but they also have to pay inflated rents to the private landlords who now own the property. Often, in emergencies or in the case of vulnerable people, the new owners have no qualms about charging double or triple the market price.

In addition, associations have been formed that “specialise” in renting housing to vulnerable people. For example, they might claim to be specialists in client groups with mental health problems, although, in reality, they are nothing more than private letting companies with little special expertise who also charge local councils exorbitant rents. They only appear to be charitable and responsible organisations. I worked in social services departments for 40 years and I have experience of these firms.

It is also worth mentioning that the council has another financial obligation closely related to this debate. Any private landlord has the right to rent their properties to people on low incomes; people who do not have the necessary funds to pay the money they demand. If the rent is not excessive, the council has to subsidise these tenants by paying them housing benefit.

Conclusion

Of course, there are a constellation of factors that influence the housing shortage and high rental costs. The problems are complex and confusing, but that does not mean we have to remain paralysed by fear or difficulty. To solve any complicated problem, you have to remove the obstacles one by one, acting in a systematic manner. Let’s take it step by step.

- The right to buy is one variable that we could eliminate immediately. Scotland has already taken this first step. In 2016, the Scottish government repealed the law completely, and since then, the right to buy has been abolished.

- Next, we could tackle the problem of tourist rental flats. Closely linked to this is the problem of second homes. For example, in Cornwall there are villages that, in summer, look like opulent London neighbourhoods, and in winter are empty and dark. The enormous proliferation of tourist accommodation and second homes contrasts sharply with the situation of many local people who cannot afford to own their own homes. Many of them have to subsist in caravans and sheds. Young people cannot leave home; they have no chance of competing for houses with wealthy people from outside the area. Cornwall County Council does impose an annual 200% council tax on second homes and the government a 5% surcharge on their purchase but these measures have had little effect.

- We could prevent speculators from leaving empty the buildings and skyscrapers that they erect. In London’s overheated market, simply leaving a building unoccupied is enough for it to increase in value faster than inflation. It is equally profitable to leave urban plots undeveloped. If we want people to repopulate our city centres, scarce building land should either be used promptly or the site compulsorily purchased for affordable housing.

- In addition, we should pay attention to uncontrolled urban expansion, a direct cause of the loss of natural habitat. This is a small island and our native flora and fauna are rapidly disappearing. The problem is exacerbated by the psychology of the English. Every English person aspires to live in a detached house or, at least, a semi-detached house with a garden. That is why there is a marked reluctance among construction companies and planning departments to encourage building upwards rather than outwards. No government has ever really tackled the problem of the advancing tide of quick-drying cement that is slowly but surely (and forever) covering the green English countryside. The south of England is becoming a vast, uninterrupted housing estate. In the south-east of this country, where one town ends, another begins. Driving around, you get the feeling that you are always on the outskirts of a town that must be just around the corner. But no matter how many corners you turn, you never reach a real town.

The government has just announced a building programme of 1.5 million new homes by 2029. But even if they ignore the serious problems outlined above and focus solely on numbers, they will still not be able to reduce the shortage in this way, for they do not even have the necessary labour force; since our departure from the EU, there are not enough builders left in the country.

We need a comprehensive programme, one that signals a change in attitude towards the problem of housing shortages: one that is fair to everyone. Such a programme would go against the values of the Conservative Party with its motto of “every man for himself ” and it would unleash a storm of protests from the property industry. And, of course, it would mean reversing Margaret Thatcher’s lasting contribution to the housing crisis, the right-to-buy policy.