(This was written in 1998 as the introduction to a doctoral thesis)

Part 1: Introduction

Galician prose fiction forms the largest part of what is a predominantly nationalist literature. As such it reflects the concerns of galeguistas, it mirrors their states of mind and it contributes to the debates within the movement. Thus it is that a comprehensive reading of Galician novels and short stories from the 1950s until the 1990s provides important insights into the changes that have occurred inside the nationalist movement since it emerged from its post-war shell. Vice-versa, in order fully to understand Galician literature from the late 1950s onwards, it is essential to have a grasp of the psychological and ideological parameters of galeguismo immediately prior to these years.

In Galicia during the harsh years following the Spanish Civil War galeguistas protected themselves psychologically by growing a hard ideological carapace which would act as a shield against the brutality of the Dictatorship. They retreated into a shell within which they took comfort in the existence of a private, separate world which was in all ways possible different to that of their Francoist oppressor.

Their protective case was comprised of two layers. The inner layer was made up of the traditional tenets of Galician nationalism that had been handed down by the founders of the movement in the mid-nineteenth century. These were the differentialist ideas that had first been formulated by men such as Manuel Murguía (1833-1923) and Benito Vicetto (1824-1878) and which found their most recent expression in the works of men such as Alfonso Daniel Rodríguez Castelao (1886-1950) and Vicente Risco (1884-1963).

According to these first principles, Galicians differed racially and ethnically from the rest of the inhabitants of Spain. In their patterns of life and the geographical distribution of their settlements they had little in common with the people of the Iberian tableland ; instead, they were close relatives of those who dwelt in the Centre and North of Europe, particularly the nations of the «Celtic Fringe», most especially Ireland. Erstwhile warriors, they were of a cyclothymic temperament: impulsive and brave but prone to bouts of melancholy. They were the descendants of restless explorers who had journeyed ever westward in their search for the land of the setting sun and who took readily to the seas, journeying to the Americas in pursuit of their their ancestral destiny: in so doing they were driven by «o anceio do alén-mar» and not by a mere desire for economic self-improvement. In matters of religion they were pragmatic. Although latterly they had adopted the Roman Catholic faith this had never truly displaced their pre-Christian animism and the two belief systems operated side by side; when the powers of the priest were deemed to be insufficient to deal with the spirit world the people turned readily to witches and wizards, the modern-day successors to the old Druidic order. Even though their ancient tongue had been replaced by just another derivative of Latin, the phonetic imprint of the gentle and lyrical substratum was still audible in their speech.

The outer layer of protective beliefs was formed from more recent matter and consisted mainly of a fresh apotheosis of the Galician peasant as the repository and retainer of the national consciousness. There had always been a tendency amongst the intellectual core of Galician nationalists, members of the urban middle class, to credit their rural cousins with an instinctive understanding that they belonged to a separate ethnic group which enjoyed a healthier and superior way of life to that which was to be found on the dry meseta of Castile, but ever since the «successful» vote in favour of the Statute of Autonomy in June 1936 it became natural for them to assume that there was a good deal of overt political awareness in the countryside and that it was largely sympathetic to the old Partido Galeguista.

From such a position it was understandable that a conviction should arise amongst some galeguistas that the tens of thousands of impoverished Galicians who streamed out of the country in the 1950s should be nurturing amongst themselves the desire expressed by Castelao in Sempre en Galiza (1944): eventually to return to their homeland as citizens of a left-leaning, independent, democratic country within a voluntary federation of Iberian states. This latter belief was fed by the remarkable stream of galeguista publications that flowed out of Buenos Aires from very early on in the post Civil War period and which included some of the most famous works of the whole movement. Not least of these was the bible of the post-war Galician nationalism, the above-mentioned Sempre en Galiza. Amongst the many other outstanding texts there were: Fardel do eisilado (1952) by Luís Seoane; A esmorga (1959) by Eduardo Blanco Amor; Memorias dun neno labrego (1961) by Xosé Neira Vilas; and Historia de Galiza (1963) edited by Ramón Otero Pedrayo.

This belief in the the left-wing nationalist potential of the many ordinary Galicians scattered throughout Europe and the Americas was also consonant with the Marxist thinking which entered Galician nationalist politics in the 1960s. Although the region was both geographically and politically only on the fringes of the European New Left, galeguista politics did become sufficiently radicalised for some to talk of a Galician proletariat, a combination of a diaspora of newly industrialised workers dispersed across the western world and those who hadn’t left home and continued to live a totally agrarian existence.

However, the idea of a revolutionary Galicia emigrante began to be called into question almost as soon as it had begun. The notion that the Galician emigrant had carried over his fervent pre-war ambition for Home Rule into the post-war period suffered a good deal of erosion in the late 1960s. It was substantially affected by the highly public disillusionment suffered by the poet and writer Celso Emilio Ferreiro, a founder member of the Marxist-oriented, Unión do pobo galego (UPG); in May 1966 he emigrated to Venezuela with the ambition of joining a revolutionary Galician proletariat in exile only to have his expectations utterly dashed by the corruption and political apathy he encountered in Caracas. At the same time Xosé Neira Vilas constantly reiterated in a series of novels and short stories that emigration was primarily the result of economic necessity and that the rural life from which the majority of emigrants came was not at all a repository of wisdom ; indeed it was often characterised by scapegoating, meanness and an obscurantist system of superstitious beliefs.

Nevertheless, amongst Galician nationalists there was no radical decline in political faith in the ordinary rural paisano until the Transition. When Franco died in 1975 there was a tremendous feeling of optimism throughout all separatist organisations and the left in general. In Galicia there were great expectations that the region could recapture the spirit of left-wing nationalism which it was widely believed had dominated local politics in the five months between the accession of the Frente Popular government in February 1936 and the outbreak of the Civil War in July.

In 1975 student life in Santiago seethed with expectation. Then came the anticlimax of the Transition, when the nationalist parties were largely ignored by the electorate. Perplexed by this snub, galeguista writers and politicians initially explained their unexpected reversal by positing that during the Dictatorship there had been such an effective brainwashing that the attitudes of June 1936 had been completely reversed: instead of wanting Autonomy, Galicians now abjured the whole idea; they had even come to despise their old selves and their provincialism. Now they placed all their faith in political parties based in Madrid; it was no wonder that they had fled Galicia in droves and wanted to put the whole place behind them. Some writers even lapsed into a petulant resentment of the Galician people for having allowed themselves to be duped or for having somehow reneged on their pre-war commitment. Other authors fulminated against the newly-elected political old guard who had been Franco’s placemen in administrations prior to 1975; the cry went up that, despite the arrival of so-called «democracy», the same Francoist veterans were still in charge.

Following the debacle and the hysteria of the transition, Galician Nationalism accepted its weaknesses, regrouped, appeared less dogmatic and slowly began to win over voters in the local elections to the Xunta. However, it had only been their initial electoral drubbing that had finally shaken them into acknowledging that they had a long way to go in order to recoup the political sway that they fancied they had lost since July 1936. Although they realised the need for a fresh political strategy, their confidence in the authenticity of the result of the vote for the pre-war Statute of Autonomy remained almost entirely intact, as it has until the present day.

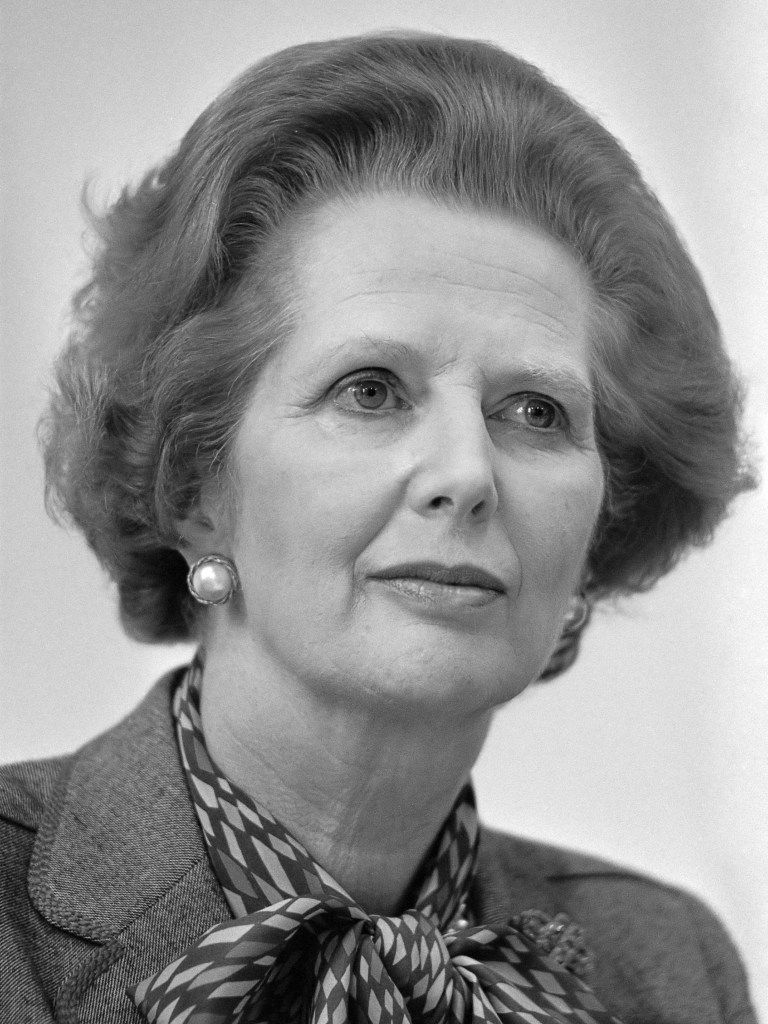

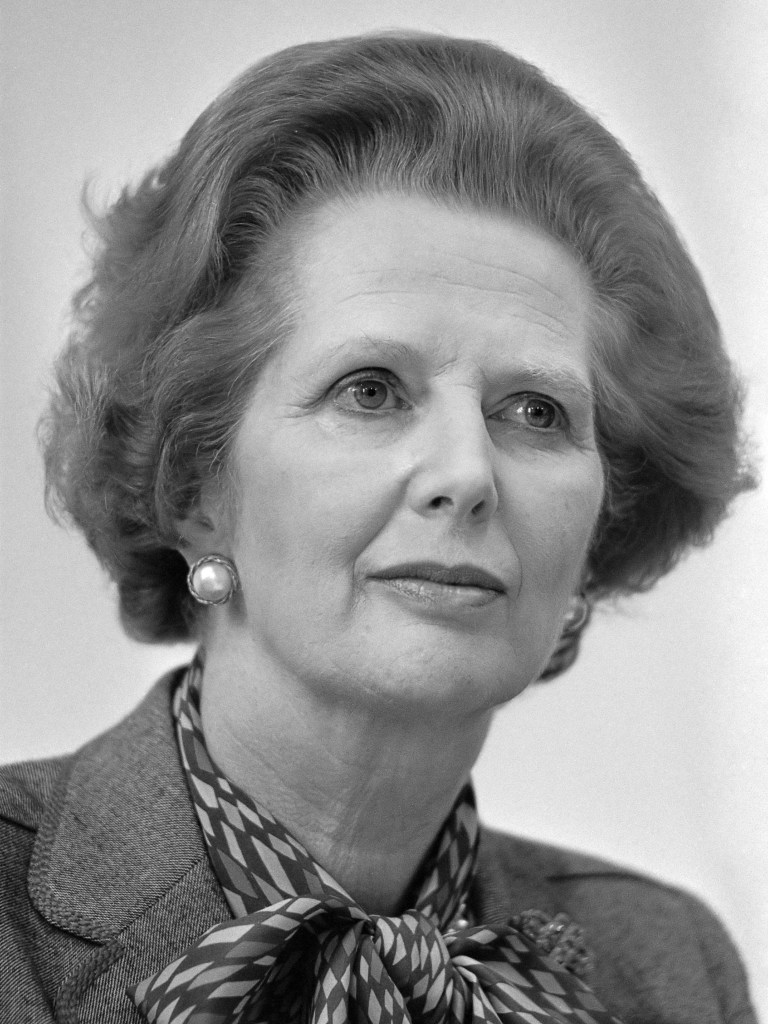

The real improvement in the fortunes of Galician nationalism can be dated to 1982, the year of the formation of the Bloque Nacionalista Galego (BNG), an alliance of small nationalist parties who agreed to suspend their ideological differences, curtail their internecine warfare and work together on a number of practical issues in an attempt to increase their overall share of the vote. This strategy has proved at least partially successful and the BNG now regularly receives a quarter of the votes in local elections. It has certainly been successful enough to prompt the governing party in the Xunta de Galicia, the conservative Partido Popular (PP), into acknowledging that the existence of regional government owes a substancial debt to the activity of the Partido Galeguista (PG) during the Second Republic. So it was that in 1994 there was the slightly bizarre situation of the leader of the PP in Galicia, Manuel Fraga Iribarne, a one-time minister in Franco’s government that had fought a civil war against the evil of the disintegration of the Spanish State, now not only embracing Autonomy but mentioning amongst his political precursors the early twentieth-century nationalists, the Irmandades da Fala, as well as Castelao, the main ideologue of the PG. It was a further irony that Fraga, after stealing nationalist thunder, was making such a success of regional government – modernising Galicia and increasing its industrial base – and that the Xunta de Galicia was being seen as one of the great successes of the Spanish devolution of power.

Although in 1982 the protective inner layer of galeguismo remained fundamentally unmodified, nationalists seemed to be placing less emphasis on the belief in the distinctive Celtic nature of Galicia. This may have had more to do with their desire to quietly distance themselves from being overly identified with a beaten race rather than any increased acceptance of the rising evidence which suggested only a mythical connection with the Celts, who in any case were no longer regarded by most prehistorians as ever having existed as a homogenous Iron Age people: Celts was a catch-all category similar to characterisation by the Romans of all outsiders as Barbarians.

The nineteenth century saw the invention by Manuel Murguía and Eduardo Pondal (1835-1917) of a large seaborne influx of Irish Celts into Galicia. Despite their elaborate contrivance of imported Hibernian mythology and their imaginative story-telling through the medium of epic poetry, Murguía and Pondal did not go so far as to fabricate the subsequent rise of any local heroes of Celtic descent. In the Twentieth Century, to make up for this lack, some authors, most notably Álvaro Cunquiero (1911-1981), extrapolated the idea of new arrivals from the Celtic northlands to include the cast of romantic characters from the Matter of Britain, thus peopling Galicia with the knights, maidens and wizards of the Court of King Arthur. It was surely not too large a leap of faith to imagine that the Britons of the fifth century — Arthur’s century — were the very descendants of the same Celtic peoples that Murguía and Pondal claimed had arrived in the last millennium BCE.

In the early 1980s Galician prose fiction registered a noticeable decline in Arthurian-Celtic themes and there was a complementary rise of the novel featuring the ordinary rural Galician as a battling protagonist. In the same year as the foundation of BNG came the first of these publications, O tríangulo inscrito na circunferencia by Victor Fernández Freixanes (b 1951). Here was a strong literary corollary of the political regrouping that was taking place.

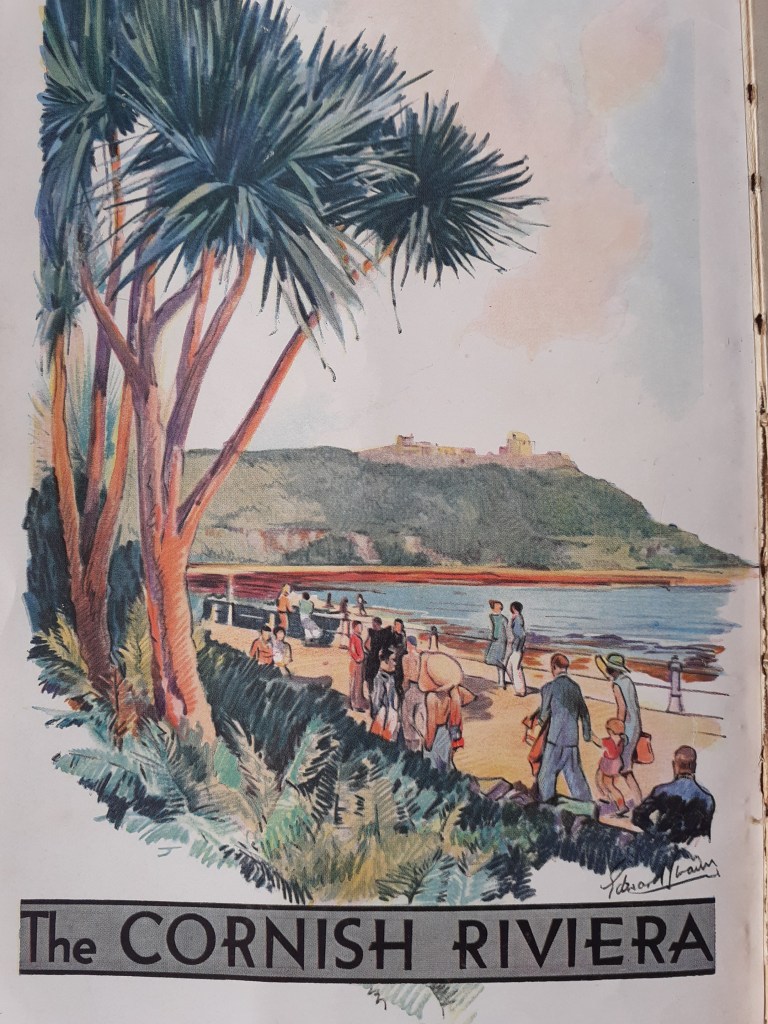

One of the basic tenets of galeguismo has always been that village life is an essential, distinguishing component of Galician ethnicity. However, due to the rapid demographic changes that had been accelerating since the late 1950s the majority of Galicians were by the 1980s living an urban or suburban existence. Despite (or because of) the ever increasing drift away from the land and the dramatic rise in the proportion of Galicians who now live in the town, there has been, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a loud literary outcry against the growing decay and neglect of the countryside. This has been matched by a corresponding increase in the idealisation in fiction of the old-fashioned but healthy, bucolic existence that was enjoyed in the scattered hamlets of the past — a strong romantic counterblast against the unhealthy stresses of modern metropolitan life.

However, such romanticism seems at odds with evidence that traditional rural life was strongly associated with poverty, deprivation, rigged elections and superstition and it was this combination of factors which accounted for two centuries of mass emigration. Galicia was an isolated, badly communicated part of Spain and had a long history of feudalism that had persisted well into the 19th century. There was no industrial revolution and the rural economy was based upon low-tech subsistence farming on land that was owned by the Church or the nobility; the land itself was split into uneconomical strips by constant subdivision and made even more unprofitable by unbearable rents and tithes. When ownership of farm land was painfully and slowly «reformed» between 1837 and 1926, tenants were given the opportunity to buy out their landlords. Needless to say, most had no money to do this and were evicted with no further ado. Wage labour was non-existent and emigration was often the only option to starving to death. In addition, Francoist oppression following the Civil War was so violent that anybody who was deemed not to have actively supported the Uprising fled abroad in fear for their lives. Even those innocent of any opposition still left for jobs in industrial centres outside Galicia. It should be said that the literature of the diaspora has concentrated more on the experience of emigration than upon its causes.

Galician writers have varied considerably in their treatment of witchcraft and superstition. Furthermore, they have not divided along ideological lines. Although several writers have continued a long tradition of providing rational explanations for superstitious beliefs, others such as Xosé Luís Méndez Ferrín (b 1938), have utilised unmodified Galician folklore of the supernatural in order to create a new brand of nationalist literature akin to Latin American Magical Realism.

The other great contemporary task of Galician authors, shared with writers throughout Spain, has been the chronicling of the years from 1936 to 1975. They have undertaken this despite the 1977 Amnesty Law, which forbids the naming of those guilty of crimes committed during the Spanish Civil War and the subsequent Dictatorship, thereby granting legal impunity to the perpetrators. Following the death of the Dictator, writers found themselves still ignominiously gagged by the new, supposedly democratic Spain; instead of enjoying the right to free speech, they remained unable to name names.

One of the earliest and best-known novels to address the sadistic treatment of Republican prisoners and to give voice to the multitude of unheard and unsung victims of the Dictatorship was O silencio redimido by Silvio Santiago (1903–1974). Ironically, like all similar novels, his work was only published because it did not redeem certain silences. Nevertheless, Santiago was among the many talented writers who sought to redress the imbalance of the previous forty years by recounting, in fictional form, the events from the outbreak of the Civil War to the years of the Transition from a galeguista perspective. Despite the limitations imposed upon them, these writers have still produced some of the finest prose fiction ever written in Galician.