Si estás planeando una visita a Londres vale la pena que pases por la casa de Dr Samuel Johnson, el célebre lexicógrafo y autor del siglo dieciocho, el hombre que aseveró famosamente, «Cuando un hombre se aburre de Londres se aburre de la vida». (“When a man is tired of London he is tired of life”)

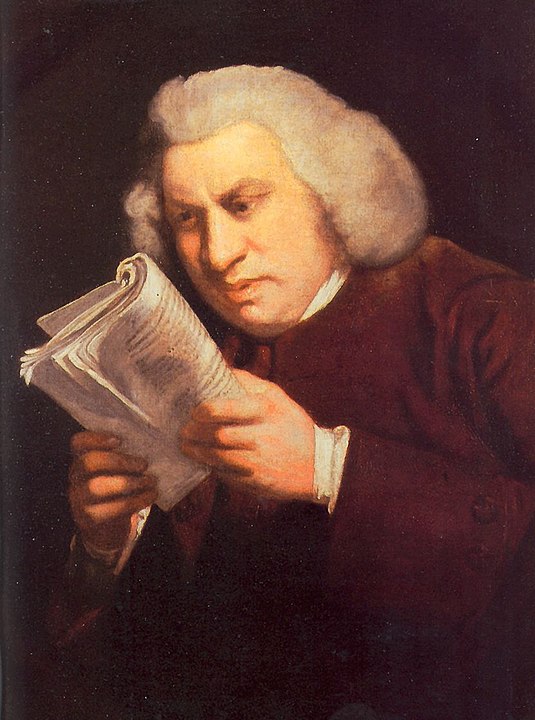

Johnson era un hombre alto e imponente con una complexión fuerte y robusta. Tenía dos características mentales sobresalientes. Padecía el síndrome de Tourette y poseía un talento fenomenal para resumir y definir: un hombre que acertaba en sus generalizaciones, acuñaba frases que todavía se oyen en el inglés moderno, e inventaba epítetos que siguen repercutiendo por los siglos.

Johnson nació en 1709 en Lichfield en el centro de Inglaterra, cursó estudios universitarios en Oxford y vivió la mayoría de su vida en Londres donde, a la edad de 39 años, un grupo de editores le contrataron a escribir un diccionario de la lengua inglesa. Hasta entonces la ortografía del idioma había sido algo caótica e idiosincrásica, la gente deletreando como le daba la gana. Incluso, a veces, la confusión ocasionada por la ortografía aleatoria llevaba al lector a malinterpretar lo que leía: tanto el sentido de las palabras como las intenciones del autor.

Johnson insistió que él no necesitaría más de 3 años para dar por finalizado el diccionario. También él lo haría por sí solo. Cuando alguien le mencionó que la Académie française había empleado a 40 académicos a lo largo de 40 años para recopilar la nueva edición de su dictionnaire, Johnson respondió de su típica manera sarcástica y mordaz: “He aquí la proporción: a ver, 40 por 40 son 1.600. Así es la proporción de un inglés a un francés: 3 valen 1.600”.

En aquel entonces los ingleses y los franceses no se podían soportar. Johnson no era ninguna excepción a la regla. Desde el siglo doce había existido entre los dos países un estado de guerra casi permanente. Todavía queda algún que otro historiador o comentarista que sigue refiriendo a los franceses como “el viejo enemigo”. (Hay que añadir que Johnson no sólo despreciaba a los franceses: tenía juicios condenatorios, contundentes y categóricos para toda persona que le contrariaba.)

El diccionario se publicó en 1755 y hasta la publicación de la primera edición de la Oxford English Dictionary en 1928 la obra de Johnson, que el casi hace por su propia cuenta sin la ayuda de nadie fuera de unas escribas, fue la biblia de la ortografía inglesa durante 173 años.

Samuel Johnson y su igualmente famoso biógrafo James Boswell se conocieron en 1773. Johnson llevaba 32 años a Boswell, un joven escocés de ascendencia aristocrática que trabajaba de abogado en Londres. Pero, a pesar de la diferencia en años, los dos hombres forjaron una amistad firme y duradera. Boswell admiraba a Johnson con una actitud casi reverencial. Algunos comentaristas dicen que, para Boswell, Johnson era una figura paterna, un hombre mayor más simpático y cariñoso que su propio padre.

Cuando se conocieron, Samuel Johnson vivía en Gough Square en una casa de la Ciudad de Londres construida en las últimas décadas del siglo diecisiete. La casa se puede visitar y es muy interesante, especialmente el último piso donde Johnson trabajaba sobre el diccionario. Aquí puedes hojear una edición facsímil. Vale la pena echar un vistazo dentro del libro porque Johnson no podía resistir la tentación de incluir sus propias opiniones y observaciones humorísticas sobre las definiciones. El ejemplo que se suele dar es de la definición de la avena: “un grano que se da generalmente a los caballos en Inglaterra, pero en Escocia alimenta a la gente”. El museo dispone de folletos informativos sobre la exhibición en varios idiomas, el español incluido. Entradas: Adultos £8, concesiones £7, niños 5 -17 años £4. https://www.drjohnsonshouse.org/

Cerca de su casa está Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, El viejo queso de Cheshire, un pub en que Johnson comía y bebía. El local se conserva más o menos igual a lo que era en el siglo dieciocho. Está señalado el sitio en el que Johnson solía sentarse. No tienes que pagar una entrada pero sería considerado maleducado que no pidieras nada de beber ni comer.

Unos años después del Gran Incendio de Londres (1666) el arquitecto de la reconstrucción de la ciudad, Sir Christopher Wren, mandó construir un monumento a la devastación, una columna erigida donde se había iniciado el incendio, una torre de más de 60 metros de altura desde la cual se daban unas vistas muy impresionantes de la ciudad renovada. La torre se encuentra a una milla al oeste de la casa de Johnson. Hoy en día el monumento queda empequeñecido por los rascacielos que lo rodean aunque para su época la torre era un gigante: tiene 311 escalones y no se puede subir de una sola tirada. Hay que parar y descansar varias veces. Aún así, la subida puede dejarte hecho polvo.

En el pasado, cuando la gente estaba menos acostumbrada a tales altitudes y tenía más miedo a las alturas el ascenso podía resultar aterrador. Una de aquellas personas a quién sí le metió miedo fue el propio James Boswell. En 1763, el año en que él y Johnson se conocieron, Boswell decidió visitar el monumento. A medio ascenso sufrió un ataque de nervios. Pero, sacó fuerzas de flaqueza y perseveró para llegar a la cima porque no quería perder la dignidad. En la cima dijo que “fue horrible estar a una altura tan monstruosa, en un sitio tan elevado, encima de Londres y todas sus agujas: «…it was horrid to be so monstrous a way up in the air, so far above London and all its spires«. Si quieres visitar el monumento tienes que pagar: adultos £5.80 y menores £2.90. No puedes comprar ni reservar entradas online. Tienes que hacer cola. Pero vale la pena. https://www.themonument.info/

Hoy en día la torre parece enano delante del edificio que hay detrás, el rascacielos, 20 Fenchurch Street, el llamado Walkie-Talkie. A diferencia del monumento, este edificio se visita gratis. Solo tienes que reservar online. No solo obtienes una vista maravillosa del Río Támesis y el centro de Londres desde la plataforma de observación sino también puedes visitar el sky-garden, el jardín exótico situado en los tres pisos más altos del edificio. También en la parte superior del edificio hay bares, restaurantes y, de vez en cuando, música en vivo. https://skygarden.london/

Si te apetece la idea de visitar las iglesias que quedan de las que Wren reconstruyó en las décadas que siguieron al Gran Incendio, puedes elegir entre las varias caminatas guiadas ofrecidas online. Por ejemplo la web de City Guides https://www.cityoflondonguides.com/tours ofrece uno de estos paseos cada martes a las 11 de la mañana. Cuesta £12 y £10 concesiones. Todas estas iglesias habrían sido flamantes edificios recién construidos en la época de Samuel Johnson y le habrían sido muy familiares. Los que quedan son auténticas joyas del Londres del siglo diecisiete. City guides también ofrece varias otras caminatas guiadas que exploran el barrio en que Johnson vivía y trabajaba.

Johnson falleció en 1784 y puedes visitar su tumba en la abadía de Westminster donde está sepultado al lado de todos los grandes de la literatura británica en El Rincón de los Poetas. Pero, ojo, los precios de entrada son desorbitados: adultos £25, concesiones £22, niños 6-17 £11, niños menores de 6 años, gratis. https://www.westminster-abbey.org/