………..or Victorian soft porn?

This sculpture belongs to the National Trust (NT). It is normally displayed at Cragside, a stately home in Northumberland owned by the Trust. This year, however, it is on loan to the Ashmolean in Oxford 21 September 2023 – 18 February 2024. In the coming year it will be on show at the Royal Academy in London 3 February 2024 – 28 April 2024. (Where it will actually be between 3 and 18 February I haven’t the slightest idea.)

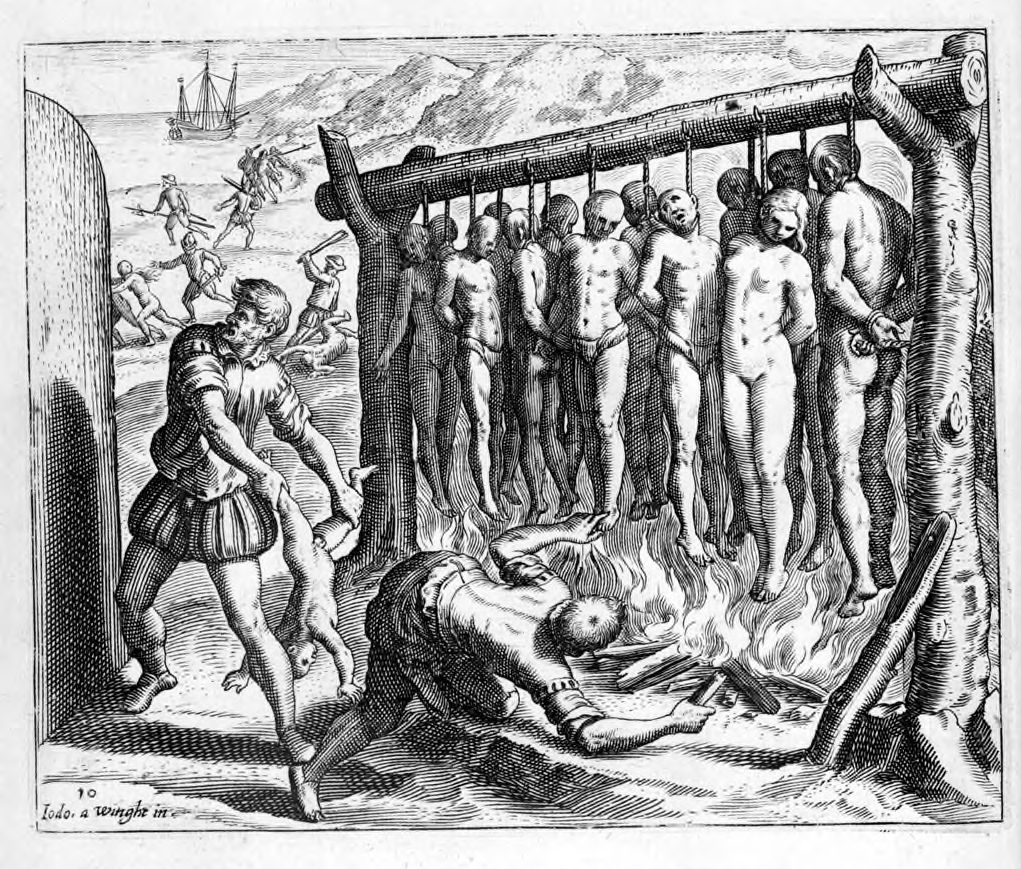

When I saw it earlier this year at Cragside, the statue was accompanied by a note which explained that the work represented “an enslaved woman standing on the West African shoreline, waiting to be transported to North America”. The note indicated that the work was a protest against slave ownership there.

It went on to say that “the depiction of her as partially nude and chained objectifies her body in a way that feels deeply uncomfortable today.”

That is, the NT suspects that there is a problem associated with the image but they can’t quite say what it might be.

The NT always has difficulty with problems associated with sex and slavery. As we have already seen in various posts, they avoid mentioning the 4,000 Chinese slaves that had to die in South American concentration camps in order to create the fortune of William Gibb, the man who built Tyntesfield, another stately home owned by the Trust. Instead of telling the truth, the directors of the NT prefer to tell the cosy little fairy tale of the nice, clever little Christian man who made himself rich from the bird poo that South American seabirds kindly left freely available on the ground. Indeed, the friendly birds made him so rich that he was able to build his beloved Tyntesfield, the luxurious mansion and gardens just outside the City of Bristol. See, for example, these posts.

https://wordpress.com/post/ingleses.blog/617

https://wordpress.com/post/ingleses.blog/181

Likewise, the directors of the NT haven’t much to say about the sexualized image of the naked girl. Whatever the NT might claim, the statue is not of a woman but of an adolescent. It seems that Mr Bell decided to depict an adolescent girl although the directors of the NT have failed to detect what is right in front of their eyes.

Just so they do know, this is the idealised and eroticised image of an adolescent African slave with her hands in irons. Only the pressure of her hands and the added weight of the irons prevents a modest scrap of cloth from falling to the floor and revealing her vagina. She is docile, humble and placid. She has an immaculate and radiant complexion and her young breasts and her curvaceous and provocative hips are perfection itself.

It is relevant here to point out that this image appears in an era in which there circulated various myths about the sexuality of black people. It was generally believed that black women were very libidinous and insatiable. They couldn’t resist the temptation of sleeping with any man. They were given to being sex slaves. As a consequence, they were very seductive and promiscuous. In the popular imagination it would have generally been assumed that this meek and mild girl would be very grateful to any man who did her the favour of releasing her from the handcuffs; or that he might prefer it if she kept the handcuffs on until she had had adequate opportunity to express her gratitude.

All this leads us to suspect that perhaps the statue might not be as innocent as the sculptor maintains. At least, it can safely be said that the statue has many of the ingredients of soft Victorian child porn. Perhaps John Bell, when he created this work, had one eye on the market for child erotica.

However, an image of a naked teenage girl was only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the sexual exploitation of children in Victorian England. The image appears in an era in which child prostitution had become an epidemic. The market was saturated with girls of a very tender age who competed for custom on the streets of London.

In 1848 almost 2,700 London girls between 11 and 16 were hospitalised because of venereal diseases contracted through prostitution. In 1875, the age of consent, which had remained at 12 since 1285, was raised to 13, in part as a result of the concern about the scale of child prostitution.

Such was the poverty of Victorian England that thousands and thousands of prostitutes of 13 years old or less walked the streets of the capital just in order to feed their younger brothers and sisters.

So, let’s not deceive ourselves. Having sex with a girl of 12 or 13 was totally legal. And the novelty of a black girl of a similar age such as A daughter of Eve, even in the form of a mass-produced miniature that sat on the mantelpiece of so many middle-class homes, could not have been better designed to sell itself to many of the men who frequented these wretched underage girls.

The image appears in an era in which Romanticism has no hesitation in combining eroticism with an admixture of suffering and premature death. Contemporaneous literature is replete with pallid female protagonists who are confined to bed, dying of incurable maladies; prostrate youngsters who patiently await their inevitable fate; pathetic figures on their deathbeds, who from time to time, let out a tragic sigh and turn their tired, hopeless and anaemic faces towards the fading light that filters weakly through the net curtains. Deserving of a special mention are the invalid women who are depicted suffering from tuberculosis, a consumptive illness which produces a wasting appearance which highlights the facial bone structure of the victim, giving her an emaciated aspect that attracts men who appreciate this particular combination of weakness and vulnerability. The Romanticism of the time had an insidious and sinister side.

The genre, with examples, is well summed up in the post by Christine Newland, The Prettiest Way to Die. https://lithub.com/the-prettiest-way-to-die/

Looking sexy while you die was not a fashion statement celebrated only in the English tradition of 19th century literature. It was found throughout the Western World around that time. Romanticism came late to Spain but it hosts some good examples. The work of Ramón María del Valle-Inclán is very impressive, especially his Autumn Sonata, published in 1902. He was convinced that there was nothing prettier than the death of a woman afflicted with consumption.

His was a morbid carnal appetite that bordered upon sexual exploitation. But Valle-Inclán was far from alone. Indeed, there has always been a percentage of men who have a sexual preference for any woman or girl who is weak, easily intimidated or at their mercy, be it for whatever reason ― debility, addiction, youth, poverty, psychological damage, illness, disability and, why not, slavery personified by a black adolescent girl in chains.

To sum up. This sexually provocative statue of a black, enchained, adolescent slave appears in an age in which the habitually defenceless, the disadvantaged women and children, were forced into prostitution to survive. The statue appears under the guise of a protest against slavery in America. However, the statue never constituted any part of any solution to anything. It was always part of the problem of the oppression of the people who made up the base of the Victorian economic pyramid. In the depths of our conscience we recognise it as an example of the exotic pornography which is calculated to sexually excite the variety of Victorian men who were attracted to child prostitution.

That is what makes us feel uncomfortable.

The studied naivete of the National Trust in the face of one of the most hateful aspects of the England of the 19th century is shameless. They seem to want to obfuscate instead of clarifying the past. They celebrate centuries of stately homes constructed by the monied classes but what they really don’t want to do is to face up seriously to the disagreeable corollaries of the time, slave labour and child prostitution included.