I used to have a psychiatrist friend who said that he had learnt more psychology from the pages of good literature than he had from any of the dried up text books in the medical library, however long he had scrutinised the taxonomies and clasifications described therein. I think that you could say something similar about the study of history. If you want history to come alive, I recommend you read a good novel.

Although it might not be his primary intention, Abdulrazak Gurnah relates the history of East Africa, from the carve-up of the continent by the Conference of Berlin between 1884 and 1885 until the achievement of independence in the sixties and the terror that ensued. But Gurnah doesn’t stop there. He deals also with the post colonial relations between the decolonised nations and their “mother country”. The latter he does through the pictures he paints of the immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers and the cold and hostile welcome that they experience when they turn up, voluntarily or out of necessity, on the doorstep of the United Kingdom. (See for example On the Beach)

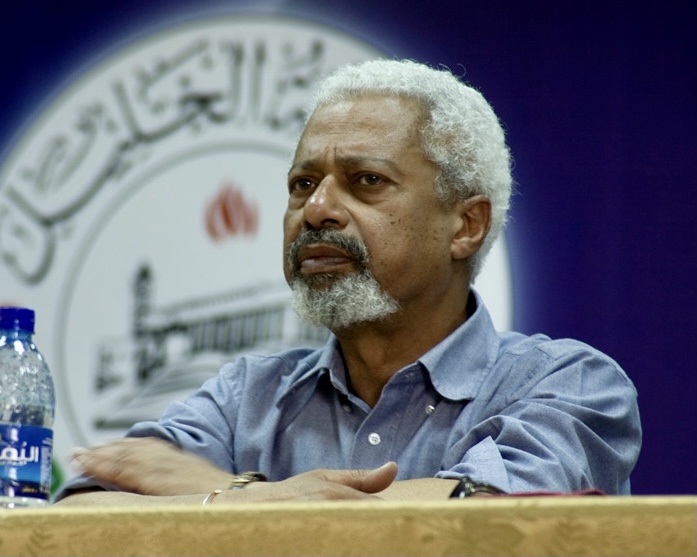

I started to read his books, just as many others did, because he had just been named the winner of the Nobel prize for literature 2021. And I was enchanted by his colourful and laberinthine novels, books that reflected the complex range of emotions, beliefs, customs, feelings and reservations of the ordinary everyday people of a muslim african culture under the occupation of an imperial power.

But not only that. His books have put into context some of my childhood experiences in England.

Towards the end of the 1950s the British economy began to shake off the enormous debt that it had been obliged to assume in order to pay the cost of the Second World War (rationing didn’t end until the summer of 1954). Until then we had to be financially very careful. Above all, our diet was very limited. We were still eating wartime recipes, we wasted nothing, we finished every meal, we cleaned our plates. But the quality of what we ate was very poor. I remember that the sausages were particularly crap, they didn’t contain a shred of meat, just a mixture of minced gristle, stale bread and unidentifiable lumps: even now when I see them on the plate they still make me gag. We were ignorant of the exotic food of our neighbours on what we called “the continent”; we didn’t know what lemons, olives, figs or mushrooms were. But we didn’t go hungry and in comparison with the privaciones that the Spanish people suffered during the post civil war period we survived tolerably well. Even so, many people here decided that life in England had become somewhat boring and monotonous: they said their lives had turned into a black and white B film and that they deserved something better, something in technicolour, something set in a climate warmer than ours.

It was no surprise that many people decided to emigrate to the Empire. We still had an empire and everyone knew that life was better in the colonies. The downstairs neighbours emigrated to Australia, others went to Canada and the most adventurous set sail for South Africa.

So it was that my uncle Edward announced one day that he had obtained a job in Dar-es-Salaam running a dealership for a well known make of car. Uncle Edward, auntie Esme and my cousins Carol and Jane spent 7 years there in Tanganyika. During their stay there the family adopted all the characteristics of expats. In their house they employed a black maid and a black houseboy and paid them both a pittance. The family changed their clothes three times a day and their sheets every morning, they criticised the food that was placed before them and had no hesitation in expressing their opinions about the psychology of the black man.

However, my uncle and aunt became very nervous when the country obtained its independence under the supervision of the British Monarchy in 1961 and they left in a hurry when finally, in 1963 the country renounced the Queen and the British Governor returned home. When they came back hurriedly to England they no longer had a house to come home to and they came to stay with us. So we had to squeeze up to let them in. During the six months we had the pleasure of living together Edward did what he could to open our eyes to the faults and defects of the black man.

He used to say things like, “The black man is a lazy man. There is only one thing he understands”, “The black man is like a child – you have to be firm but fair with him”, “The blacks are not ready for independence. Nothing good will come of it. The communists will take advantage of their gullibility. It won’t work”, and “When it’s all said and done, the blacks prefer to work for a white man.”

My uncle’s opinions were identical to those of Frederick Turnah, a Victorian character in Desertion, one of the best novels of Abdulrazak Gurnah. The book begins in 1899. The British have just taken control of Zanzibar, Kenya and Uganda, the latter two being new countries invented by the Conference of Berlin, the conference that sanctioned the allocation of the regions of Africa which had not as yet been appropriated formally by any of the European powers. On assuming the administration of its new colonies, the British abolished slavery, the activity which had made a fortune for the previous owners of the coastal region, the arab sultans of Zanzibar. However, abolition brought with it a big problem: the freed people were reluctant to work for the British. In the words of Frederick Turner, the colonial government’s local administrator: “In slavery they learned idleness and evasion, and now cannot conceive of working with any kind of endeavour or responsibility, even for payment”. Burton, a friend of Turner and manager of a British estate, is of much the same opinion: “You can only make them work by coercion and manipulation, not by making them understand that there is something moral in working and achieving”. In addition, Burton liked to predict the slow disappearance of the lazy, savage negro and his replacement by the energetic european colonist. He was convinced that “the blacks” were a race on the road to extinction. For Burton, and many others who shared his dream, the future of Africa would be like that of the USA, a whole continent peopled by European immigrants.

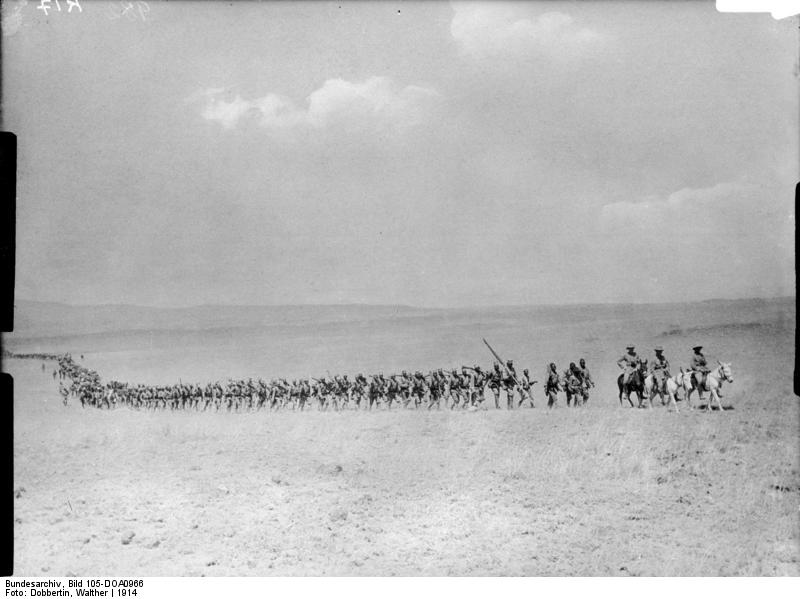

At the same time that the Conference of Berlin granted the countries of Uganda, Kenya and Zanzibar to Great Britain, it assigned Tanganyika to the Germans as their own “sphere of influence”, one of the more notable euphemisms of the 20th century. The tribes in the interior of the country didn’t have the slightest intention of allowing anyone to dominate them and in his novel, After Lives, Gurnah describes the German reaction to the intransigence of the autochthonous people. Instead of carrying out a policy of ingratiating themselves with them, for example, installing supplies of clean water, opening schools for the children o assisting them with agriculture, the Germans treated them worse than stubborn animals: they carried out a policy of selective extermination: a strategy of mass killings, public executions and the elimination of entire native peoples by the use of a scorched earth campaign.

After Lives also shows us the pathetic spectacle of how, during the First World War, native troops were tricked or forced into fighting a foreign war by distant European countries that didn’t give a shit whether they lived or died.

During the 1950s, in neighbouring Kenya, the British army suppressed the nationalist insurrection with great brutality, employing much of the strategy that the Germans had previously used in Tanganyika. The British government approved the practice of torture. At least 11,000 indigenous people died, a figure that includes the hanging of 1,090 rebels at the end of the war in 1960.

As a result of the defeat of the Germans in the First World War, Tanganyika became a further British possession. My uncle and aunt arrived there in the fifties, just four decades after the expulsion of the Germans, but it never occurred to them that the violent behaviour of the Aryan master race might have been a determining factor in the antipathy of the black population towards Europeans. In the same way, my uncle and aunt despised the ambitions of the Kenyan pro-independence supporters. How could such a childish people ever hope to govern themselves? They got what they deserved.

My uncle and aunt believed that, with independence, the native population of Tanganyika had turned openly ungrateful towards its British benefactors and this was surely the result of the influence of the communists.

All their opinions were widespread in the UK during the decades which followed the Second World War. It is not surprising that the africans and the afro caribbeans that arrived here during this time felt themselves to be personae non gratae.

Finally, my uncle and his family also left our house, giving us back our independence. Throughout the six months that they had been with us, my uncomplaining mother had worked very hard to meet their colonial standards. After six months of cooking, doing the washing and ironing for everybody, she began to refer to her brother as “the black man’s burden”.

Only three of Gurnah’s novels have been translated into Spanish and they are not always easy to get hold of. Paradise (Paraiso), On the Beach (En la orilla) and Admiring Silence (Precario Silencio).

If you fancy reading Paradise in Spanish, a Kindle version has just been published at a very reasonable price. The novel is an attempt to recreate the East Africa of the years between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the First World War, the period in which the region was being split between Great Britain and Germany, the age in which names were given to the great expanses of Africa “granted” to every western european power represented at the Conference of Berlin. Gurnah recreates this period by telling the story of an epic trading expedition on foot to the interior of the continent. The novel is set in Kenya, Tanganyika and what is now called the Democratic Republic of Congo. It is almost an imagined documentary of a lost time.

Throughout Gurnah’s work the reader must familiarise themself with the Swahili words that pepper the page. Gurnah rejects the idea of a glossary, believing that a translation to another language would impoverish his linguistic portrait.