You come out of this museum remembering positive things. Most of all you recall the love and respect that second and third generations of immigrants have for their parents and grandparents. And just how proud they are of the useful contribution all their relatives have made to this country.

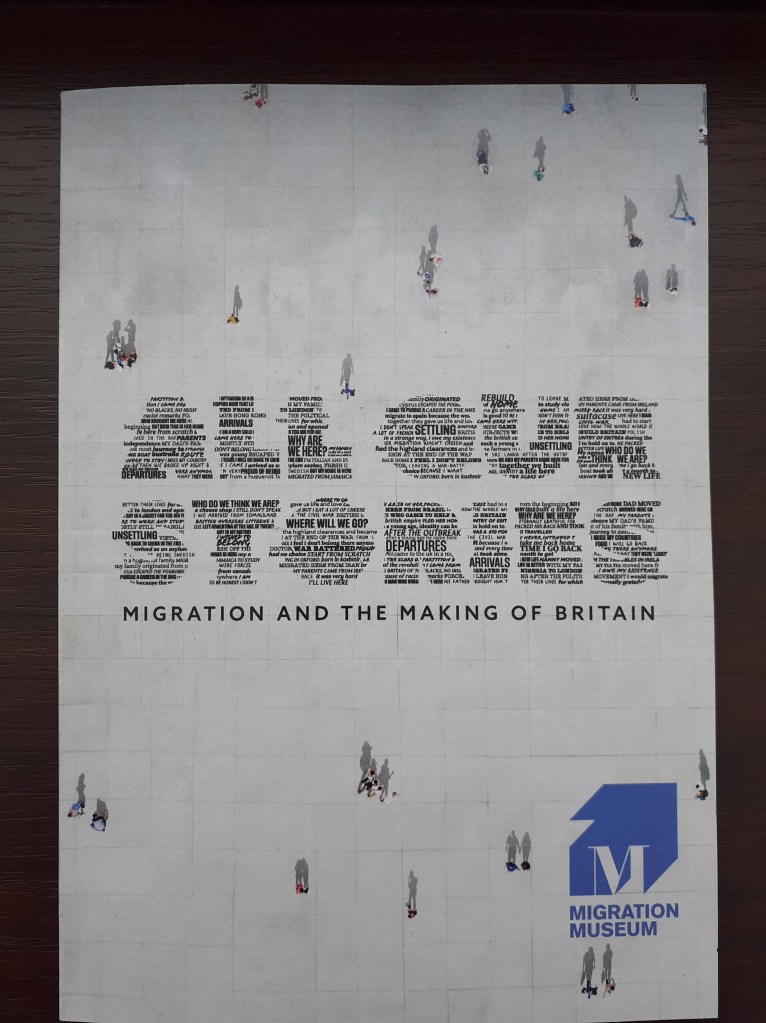

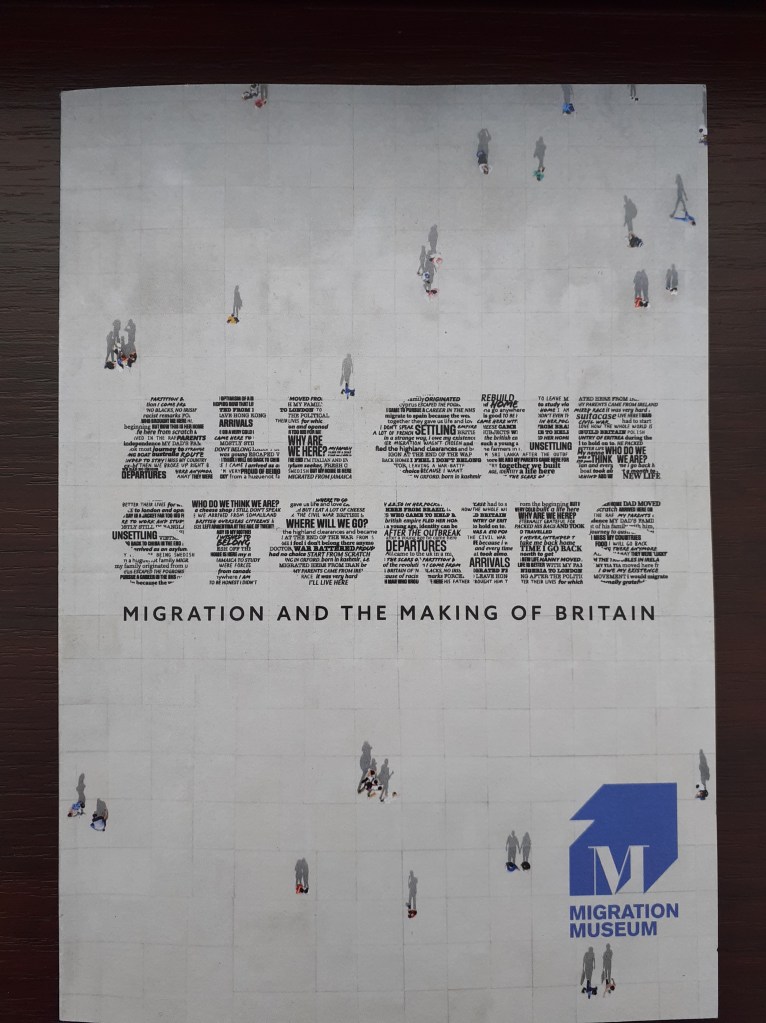

The current exhibition, All Our Stories, «brings together the Migration Museum’s work over the past decade and more, alongside new stories that highlight just how central migration is to our lives».

The quote above is from the book All Our Stories that accompanies the exhibition. More than a pamphlet and less than a book, the 50-page publication will only cost you a donation, but buy it because it encapsulates everything about the subject and is an essential explanation of the spirit and nature of the museum. Its articles on the museum’s work are very succinct, distilled and informed and clarify the many terms that characterise the immigration debate.

The museum’s message is easy to assimilate.

As George Alagiah, the recently deceased BBC correspondent and presenter who was born in Sri Lanka, grew up in Ghana and became an adult in England, said, the museum is ‘a place where the story of Britain is told in all its colour and variety. A United Kingdom of peoples. That’s what the Migration Museum represents.’

That’s what the museum does: it focuses on the personal stories of migrants and their families. It shows that we are all the same, whatever our ethnicity, our colour or our religion. We are all members of one another.

Start your visit by watching the short film that has been prepared about the history of this little piece of cold land that was not even habitable until 10,000 years ago, the time when the ice melted and our ancestors were able to arrive from the European mainland. Yes, from the moment the first human set foot on this island, we are all immigrants. The film concludes by talking about the new arrivals from Ukraine. (Let us hope that finally our governments in the West will keep their word and give them the military aid they need so that they can do what they long to do: return to their own country. But that remains to be seen).

The museum avoids being rancorous and vitriolic. That doesn’t mean it shrinks from pointing out the shameful way we treat many immigrants and how we use them to divert attention away from our own political and economic failures.

For example, the Chart of Shame exhibit, shows the front pages of the British press in the run-up to the notorious 2016 referendum on our continued membership of the European Union. It demonstrates that, instead of analysing the possible dire economic repercussions of excluding ourselves from the world’s largest trading bloc, the press helped turn the whole thing into a vote against immigrants. Liz Gerard, another journalist, made a collection of all the front pages of the national newspapers that year in which 287 of them carried a hostile headline indiscriminately aimed at the presence of more or less any foreigners in our country.

Liz Gerard describes the attitudes of the headline writers as follows: «Journalists know very well the differences between EU and non-EU migrants, between refugees, asylum seekers and illegal immigrants – but some were, and still are, happy to create an overall impression of one amorphous mass hell-bent on invading our country and changing our way of life. It is easier to blame ‘the other’ than ourselves for all that is wrong in our society. And it shames my trade.»

The message of the museum is that the history of this country that the newspapers hand out is deliberately upside down and to make sense of it we have to turn it up the right way. Only then can we see that it is not true that migrants depend upon us, but that we depend upon them. In other words, without migrants, we will never achieve anything. They are the doctors and nurses in our National Health Service; they work in our laboratories; they are our scientists and inventors, our bus and taxi drivers, our musicians and authors; they are in charge of our hotel and catering industry; they are the staff of universities, teachers and professors; they are television presenters and correspondents; and they play an essential role across the whole range of British industry; they are factory workers, farm workers, home helps, and office and domestic cleaners. They comprise the majority of regular Premier League players of our national sport. So much so, that 9 of the 11 starters in the England squad for Euro 2024 were the children and grandchildren of immigrants. If they had been excluded from the national team only John Stones and Phil Foden would have been allowed to play.

The museum reminds us that millions of us have also left our home country and moved to other parts of the globe. We must never forget that we are all migrants, the British included. David Olusoga, the historian of slavery and racial discrimination, says on page 52 of All Our Stories that ‘one of the most astonishing and significant statistics on migration is perhaps the least known. Between the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, 22 million British people sailed off to become citizens of other countries or citizens of British colonies’.

The museum does not engage in political campaigning. It does not offer solutions to the logistical problems faced by government and immigrants alike. The exhibitions limit themselves to bearing witness to the good and bad experiences of migrants. The museum does exactly what a good museum does: it teaches everything related to the central theme. But it steers away from being directly political.

The difference between this and a more traditional, historical museum is that the issues that are focused on and addressed here are present, current, happening now, real and burning, and many of them have yet to be resolved.

The thing I have never quite understood is why, for the most part, asylum seekers do not have the right to work while they are awaiting the resolution of their particular case, an embargo that produces a whole series of absurd problems. This percentage of migrants often arrive here penniless and homeless. The number of people stuck in this category varies from month to month but the government estimated at the end of March 2024 that, at that time, the number was over 117,000. Although the government does not give them money, it does accept the responsibility of housing these people and feeding them. This results in the creation of a private accommodation industry (not always of acceptable quality). Many asylum seekers wait more than a year for a decision on their future. During this period they are not allowed to look for work and the ensuing long wait can have a very demoralising effect. Also, this accommodation costs an arm and a leg, something that gives rise to resentment not only among British racists, but also among the ordinary public. At the same time as these asylum seekers have nothing to do, the UK is experiencing a long-term labour shortage. That is why the situation is absurd.

However, the situation can be improved. It doesn’t have to be like this. It would be easy to give asylum seekers permission to work by giving them a social security number that would give them the opportunity to look for work and, hopefully, feel appreciated. At the same time the Ministry of Labour and Pensions could monitor their movements using the same number. Job vacancies would be filled, employees would receive a salary, find their own accommodation and pay their own rent. It would be a win-win situation.

Last but not least is the educational function of the museum. Every year thousands of primary and secondary school students pass through its classrooms where they learn the positive value of migration. In its new home in Fenchurch Street in the centre of the City of London in 2027 the museum will enjoy larger and more sophisticated teaching resources, capable of accommodating more than 20,000 students annually. It will also run, as it already does, teacher training courses, and more general programmes on social inclusion and integration.

At the moment the museum is located in the Lewisham shopping centre in south-east London where it fits in well in this multi-ethnic neighbourhood. It is also easy to get to. It’s only 300 yards from the DLR.

But you don’t have to wait till 2027. Visit now and don’t miss the current exhibition. It is an antidote to the lies that are so destructively promulgated in the media. And don’t forget to visit the bookshop. They have a wide range of books on migration.

Links

Migration Museum: https://www.migrationmuseum.org/

The Centre for Global Development: #LiftTheBan: Why UK Asylum Seekers Don’t Have the Right to Work #LiftTheBan: Why UK Asylum Seekers Don’t Have the Right to Work | Center For Global Development