It was the arrival of the railway that marked the beginning of tourism in Cornwall. The first line to London opened in 1859. Initially, it transported copper and tin ore, agricultural and dairy products, kaolin and fresh fish. The only passengers were businessmen and mine owners. During the 1860s, the copper and tin market collapsed dramatically as a result of new competition from South America, especially Chile. But as Cornwall’s mining industry declined, tourists began to arrive, holding out the possibility of a profitable future for railway companies.

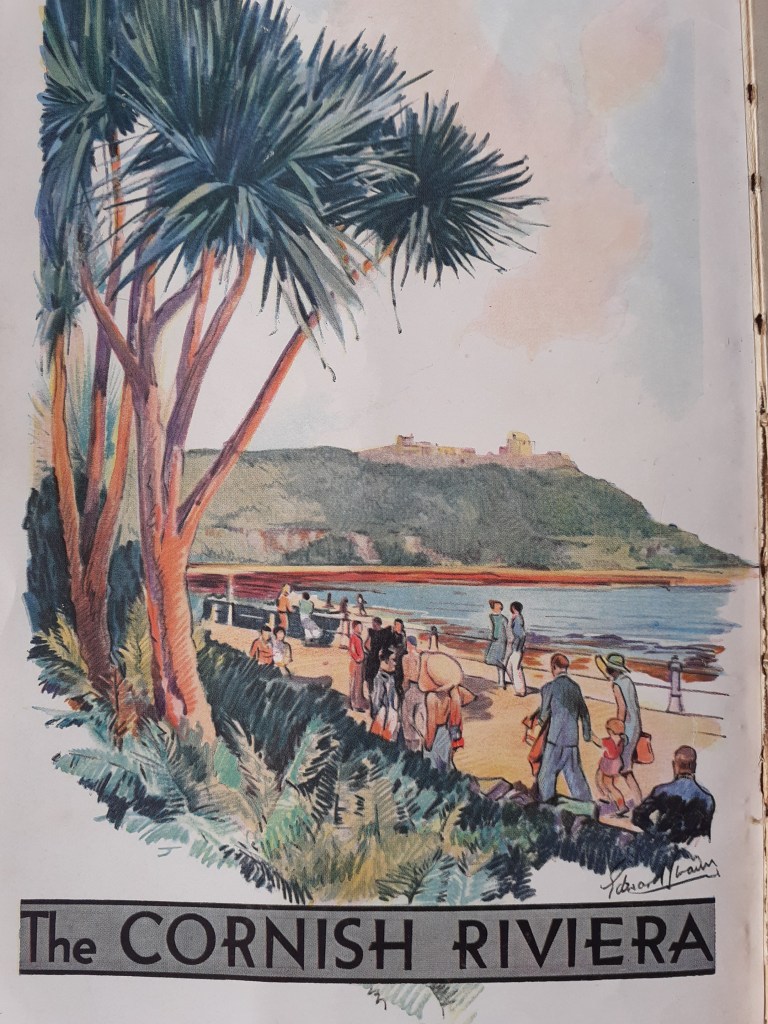

So it was that the Great Western Railway (GWR) did everything it could to promote this new socio-economic lifeline. In 1904, GWR coined the term “Cornish Riviera” and named one of its trains after it: the Cornish Riviera Express began service from London Paddington to Penzance in the same year, taking seven hours and twenty-five minutes to reach its destination.

In 1928, almost a hundred years ago, the GWR published its very own guide to Cornwall entitled ‘The Cornish Riviera’, which once again falsely implied that the climate of this part of southern England was similar to that of southern France.

The author of the book was full of praise for the county and made special mention of the climate, saying things like:

The simple truth is that in Falmouth it is as warm in January as it is in Madrid, and as cool in July as it is in Leningrad…..

Penzance is proving a formidable rival to Madeira, the Scillies to the Azores, and Mullion to Monte Carlo.

And so began a whole mythology about the climate of Cornwall.

Oh dear! This was not only misleading, but also painfully inaccurate, and could even have damaged the GWR’s argument if the public had been more aware of the true nature of recent winters in Madrid. For example, in 1914, a few years before the publication of this book, January in Madrid was so cold that the lake at the Crystal Palace in the Retiro Park froze over, serving as an improvised skating rink for weeks. In the very winter of the book’s publication, the Spanish capital was once again covered in snow.

In southern England, the climate is generally wet but mild. Winters are cold and windy. However, there is a slight regional variation in the weather. There is always more wind and rain on the Atlantic coast, but the further east you go, the less rain you will find. In the town of Penzance, located near the western tip of the county, annual rainfall is around 1200 mm, while in the city of Norwich, located at the easternmost point of the country, annual rainfall is only around 732 mm. Also, in the south-east, summer temperatures are about 4 degrees Celsius higher than in Penzance. We are talking about average temperatures, but the actual difference in summer can be much more dramatic. One week in August, while we were on holiday on the Thames estuary, the temperature was 30 degrees: in Penzance, people were shivering in just 17 degrees.

But yes, it can be said that in Penzance the winter temperature reaches around 8 degrees Celsius, which is higher than in other towns further east. It is true that it rarely freezes in Penzance; it is not so cold that its imported Mediterranean plants die. That is why, technically, and only technically, the term subtropical can be applied to Cornwall. This technical term has been exploited unscrupulously by companies eager to sell holidays in the “subtropical paradise” of Cornwall. Woe betide anyone who arrives at their hotel in March expecting to spend the week lounging by the pool, sipping margaritas and surrounded by tropical jungle. The truth is that it is cold and it rains a lot. Remember the picture of the seafront? Norman Gaston has captured the essence of a typical winter’s day in Penzance.

However, local tourism boards, hotels, tourist offices and all social media insist on repeating the term like parrots, unable to understand its true meaning; although the facts categorically deny it, the myth of a Mediterranean or subtropical climate has stuck in the public’s mind.

A century after the advertising campaign launched by the GWR, Cornwall continues to enjoy the myth of its exotic climate. In fact, the myth has prospered. Cornwall has become such a desirable holiday destination that companies compete to associate themselves with it. What was once nothing more than a remote, rocky promontory perpetually shrouded in mist and drizzle, a poor Atlantic cape buffeted by the wind, is now portrayed in advertising as a sunny Shangri-La surrounded by blue seas, a paradise where time stands still in an atmosphere of peaceful excellence and value for money. If it had a corporate slogan, it would resemble the simple motto that the Galician regional government has been promoting for several decades: “Galicia, Calidade” (Galicia, Quality). No company does this better than Seasalt, a famous retailer of casual wear. Take a look at their website. But beware, although they are based in the Cornish town of Falmouth and their advertising only contains views of Cornwall captured on sunny days, their primary manufacturers are not Cornish; their garments are made in exactly the same places as those sold by their competitors: India, Turkey, China, Vietnam, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bulgaria.

In the interwar period, the GWR was proud that its mode of transport was the fastest and most comfortable way for the new middle-class tourists to travel to their destination. However, the company was also increasingly aware that a new era was dawning and that it should not ignore the boom in the motor industry. As a result, it intensified its advertising campaigns. In addition to its collection of tourist guides to all of its destinations, GWR produced a series of posters in various styles that are still very famous in this country; hundreds of thousands of reproductions are still sold every year.

The romantic literature of the interwar years, especially the many novels by Daphne du Maurier set in Cornwall, helped to undermine the hegemony of the railway. The most famous of her novels are Jamaica Inn (1936), Rebecca (1938) and Frenchman’s Creek (1941).

During the Second World War, people enjoyed reading these literary creations, and in the years immediately following the cessation of hostilities, the idea of discovering the most remote areas of their own country by car captured the imagination of a whole new class of people: car owners. The best of these novels was Rebecca which was made into a film by Alfred Hitchcock in 1940. Shot in black and white, it is the cinema version most faithful to du Maurier’s chilling Gothic novel.

Both the novel and the film show the desperation of the villain, Maxim de Winter, in his mad insistence on driving his classic convertible car to London and back in a single day to consult his solicitor, crossing the entire south of the country in one go on the primitive and rather slow road network that existed in the 1930s. See the actual car here: https://imcdb.org/vehicle_62913-MG-SA-Tourer-Charlesworth-SA1407-1937.html . Chat gpt estimates that at that time, the one-way journey by car from St Austell, a fairly accessible town in Cornwall, to central London would have taken between 9 and 12 hours, or even longer. Of course, du Maurier wrote with poetic licence, but people believe what they want to believe, and the mere mention of the words “car” and “Cornwall” side-by-side, served to stimulate the ambitions of all new motorists. It gave the impression that such a trip was feasible. That’s not to say that everyone wanted to replicate Maxim de Winter’s feat, but with a few stops along the way in picturesque villages, Cornwall could be a great destination.

Then, to further whet the reader’s appetite, came the Poldark saga written by Winston Graham, a series of 12 novels published between 1945 and 2002. This saga has been not only one of the most phenomenal popular literary successes of the 20th century, but also one of the most watched series on the BBC. There have been 43 episodes across 5 television seasons.

The saga has it all. It is an informal history of Cornwall that deals with the events of the 18th and 19th centuries and the social relations of the time: the divisions between the landowning nobility, the poor people who work for them, the copper and tin mines, the conflicts between the owners and the miners, 19th-century politics, labour reform, the American War of Independence, the French Revolution and much more. It also includes the essential love triangle and all the possible conflicts engendered by inheritance. In other words, all the ingredients of a real soap opera. As for the popularity of the television series, the performance of the very handsome Aidan Turner, who played the role of Ross Poldark for the last few seasons, cannot be overlooked. The other major protagonists are the landscape and the weather: the raging seas, cliffs and storms reflect the inner turmoil of the characters and the untamed spirit of the region.

Another major «influencer» and contemporary of du Maurier and Graham was the famous North London poet John Betjeman. In 1908, at the age of two, Betjeman accompanied his family to Cornwall for the first time. From then on, they visited the same place every summer, accompanied by their maid. They stayed in the small village of Trebetherick in the north of the county. Although this village was closer to London than Penzance, the branch line was slower than the main line, so the steam train took up to nine hours to complete the journey from London Waterloo to Wadebridge, the nearest station to their final destination. When they arrived in Wadebridge, the family still had to endure a two-hour journey by horse-drawn carriage along a rough, unpaved road.

For a poet, Betjeman was very popular, especially amongst the middle and upper classes. They liked him a lot. They found his television series very affecting and nostalgic: programmes about churches, architecture, the Victorian era, steam trains, the leafy north of London (especially Highgate), pretty English villages and the countryside (especially Cornwall). When visiting these places he loved so much, Betjeman was comfortable and comforting, funny and good-humoured. The influence of his childhood memories of holidays in Cornwall and the growth of tourism should not be underestimated. His many television appearances until his death in 1984 helped to create a refined and well-off holidaying public from London and the Home Counties. Today, if you sit quietly and eavesdrop on conversations in Cornwall during the high season, in the most expensive pubs in the style of the «good old days» or in the most bohemian cafés perched on the clifftops, you will still hear talk of nannies and houses in Portugal: all spoken in southern English accents, most noticeable those of the wealthy north and west of London. These people reserve for themselves the most exclusive coves that, during high season, become a sort of Kensington-on-sea or Highgate Beach. Betjeman’s comforting influence is still there, and his small, affectionate and welcoming Edwardian summer world lives on.

Naturally, with the arrival of so many wealthy tourists and immigrants, the price of housing is now well beyond the means of local people. A significant percentage of homes in the county are now tourist rentals, second homes or houses built by English immigrants. Interestingly, the area most affected, where the percentage has reached 70%, are the parishes around Trebetherick, the very place made famous by John Betjeman.

Although they are very different places, the causes of homelessness in Cornwall are the same as those in the Balearic Islands. I recently saw a documentary by the German broadcaster Deutsche Welle entitled ‘The dark side of tourism: the property crisis in Mallorca’, which is still available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzsZTYv93Fg. But, curiously, the documentary barely mentions the enormous proliferation of second homes in this popular tourist destination. In Mallorca, for example, the average price per square metre for the sale of homes is €6,000/m². The number of wealthy owners from northern Europe is phenomenal. Every month, hundreds of Mallorcans have to flee to the mainland because they cannot afford to compete with wealthy outsiders. In other words, homelessness is a problem with two causes which are closely linked: the immense proliferation of tourist lets and second homes. If you want to protect the local population, you have to tackle them together. In Spain central, regional and local governments are doing nothing.

In Cornwall, as we noted in the previous post on the housing crisis, there are villages that, in summer, resemble affluent London neighbourhoods, but in winter become sad, empty and dark places. The enormous proliferation of tourist accommodation and second homes contrasts sharply with the situation of many local people who cannot afford to own their own homes. Many of them have to subsist in caravans and sheds. Young people cannot become independent; they have no chance of competing with wealthy people from outside the area. The local government (Cornwall County Council) imposes a 200% surcharge on property tax for second homes, and the national government imposes a 5% tax on the purchase price, but these fiscal measures have little effect. The invasion continues unabated.

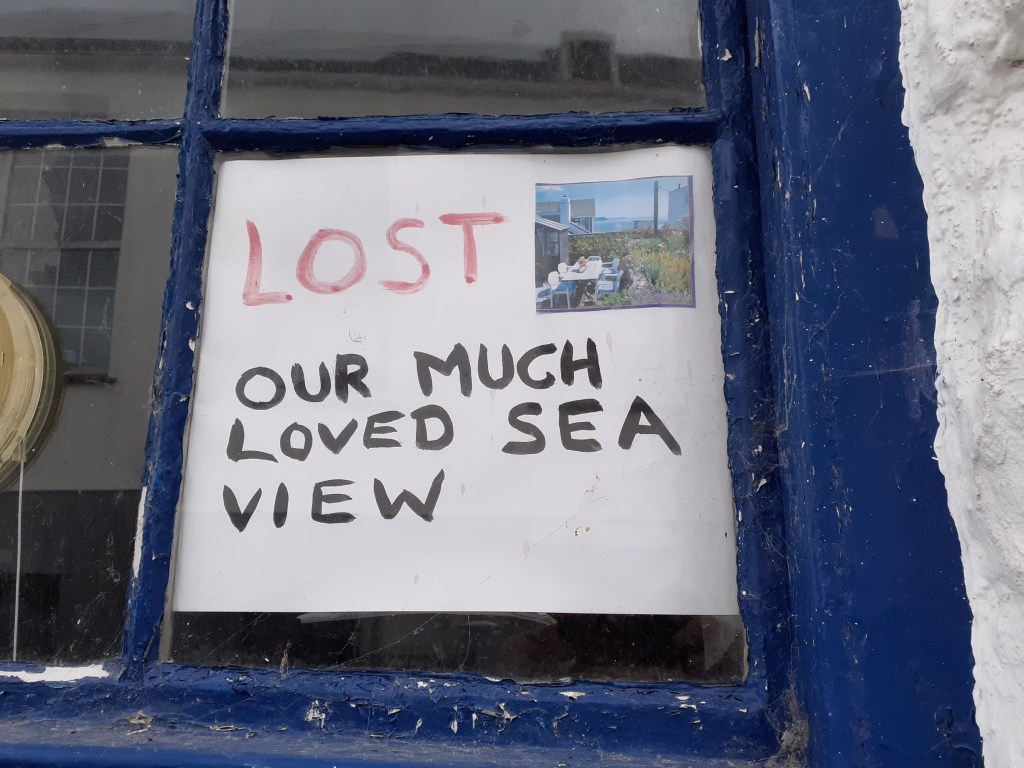

Imagine that for generations your family has enjoyed a little house by the sea in a small picturesque fishing village. However, one day a new wealthy family arrives and takes advantage of the narrow strip of land between the beach and your old house to build their new dream home. So it is that you lose your prime spot on the coast forever. All that remains of your sea view is this small photo in the window and the sad memory of something you will never get back.

And we have to talk about traffic.

When I refer to Maxim de Winter’s reckless exploits, I am not saying that one of the characters in a novel by an English author who wrote a novel in the 1930s was responsible for the current traffic chaos one encounters on the narrow Cornish roads, but I had to start somewhere.

Cornwall is a beautiful place, but it is very, very small: a peninsula of just 3,562 km², a tiny piece of land compared to its Atlantic cousins: Galicia 29,574 km² and Brittany in France 27,209 km². And beyond the recent improvements to the main roads, the rest of the map is a network of fairly narrow country roads. The closer you get to the coast, the more delicate this web of lanes becomes. Although they are now covered with tarmac, their dimensions are more or less the same as they were a hundred years ago and they cannot cope with the congestion produced during the high season. The current population of Cornwall is estimated at 600,000, plus the 4 or 5 million visitors that arrive each year, a third of them during the peak summer season. And for the most part, they arrive by car. Summer traffic jams are legendary, and when a traffic jam encounters a tractor coming in the opposite direction, reversing is at once comical, long-winded, exhausting, tedious and time-consuming, and involves a tremendous overdose of frustration for everyone involved.

It should also be mentioned that house prices are not the only things that have risen so sharply. Prices for everything have become stratospheric. The knock-on effect of so many visitors has been to create inflation in all local prices. A couple of examples:

The cost in Padstow (located on the other side of the River Camel opposite Trebetherick) of takeaway fish and chips sold in a shop named after the famous chef Rick Stein is double the national average. This year, his takeaway cod and chips will set you back £21. Not only do you have to pay a fortune, but you also have to find a place to eat your food, cradling it in your lap and trying not to spill it. If it rains, you’ll have to eat it in your car, but then the car will smell of stale fish and chips for the rest of your holiday.

I have noticed that in some places with a large tourist influx, there is a dual economy. I first noticed this about 15 years ago when the person serving in a small shop near the setting of Frenchman’s Creek asked me, ‘Are you local?’ He implied that there was one price for locals and another for visitors. I had to confess that I wasn’t, and as it turned out, he charged me double.

Second example. If you are on holiday and it is raining, and you are contemplating the perennial problem of what to do with the kids when it is raining and it is impossible to take them to the beach, well, why not grab your umbrella and head to King Arthur’s castle? You can’t have forgotten how the mythical king is supposed to fascinate children? Since the invention of the myth, and with little evidence to go on, many towns have competed for the honour of being the headquarters of the supposed King Arthur. But here in Cornwall you have the current market leader, the much-heralded and highly publicised Tintagel Castle. Although the remains of the castle are nothing more than a few piles of stones, the admission prices alone should convince you of the authenticity of Tintagel’s claims to be the real fortress of the one and only King Arthur. This year, a family ticket will cost you £58.

Architectural evidence suggests that the castle was not built in the 6th century during the heyday of the supposed King Arthur, but rather during the Norman period. Another Norman castle from the same period that is managed by the same company, English Heritage, is Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire. The castle is in much better condition than Tintagel Castle, and the entrance fee for a family is £28.60.

Once upon a time the coast was free for everyone. Now everything has a price, and the price of everything is sky-high… This is the problem with overtourism, wherever it occurs.