If you are planning a visit to London why not drop in at the house of the celebrated 18th century author and lexicographer, Samuel Johnson, the man who most famously said, “When a man is tired of London he is tired of life”.

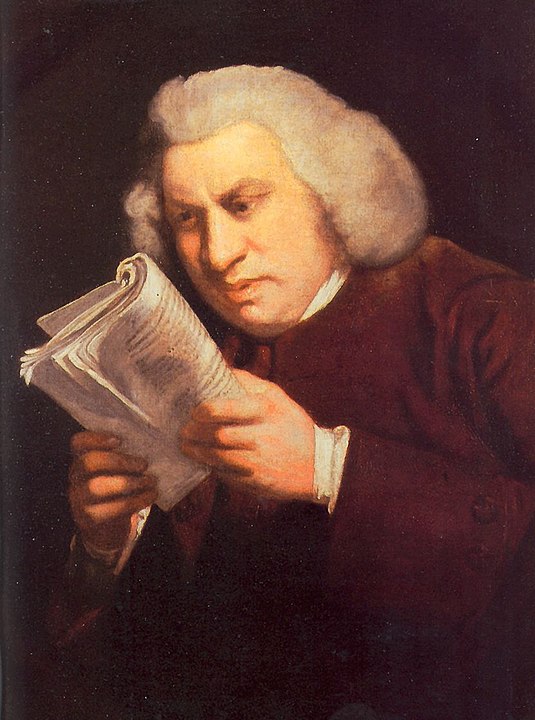

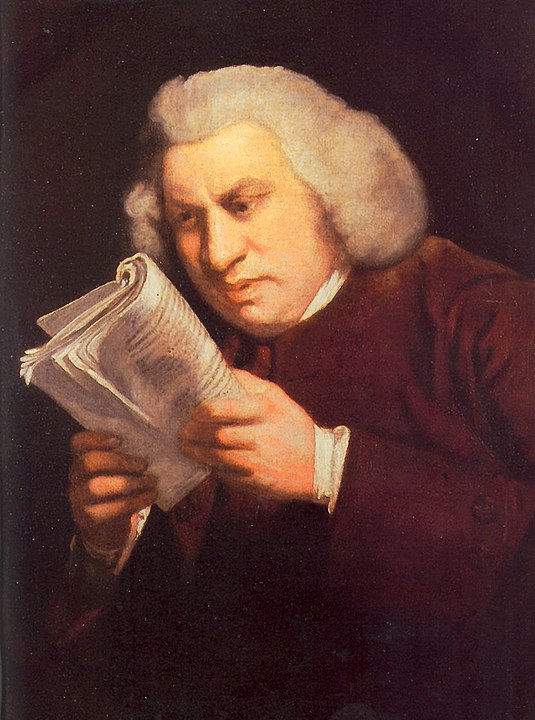

Johnson was a tall and imposing figure with a strong and robust constitution. He had two outstanding mental characteristics. He suffered from Tourette’s Syndrome and had a phenomenal talent for summarising and defining: a man who hit the mark with his generalisations, coined phrases that are still in use in modern English and who invented epithets that have echoed down the centuries.

Johnson was born in 1709 in Lichfield in the English Midlands, he studied at Oxford University and lived the greater part of his life in London, where, at the age of 39 he was commissioned by a group of publishers to write a dictionary of the English language. Until this time the spelling of the language had been somewhat chaotic and idiosyncratic, everyone employing their preferred letters in the order that they felt fit. Sometimes the arbitrary orthography led readers to misinterpret what they were reading, so much so that sometimes they lost the sense of the words or misconstrued the intentions of the author.

Johnson insisted that he wouldn’t need more than 3 years to complete the dictionary. He would also do it on his own. When somebody mentioned to him that the Académie française had employed 40 academics for 40 years in order to compile their dictionnaire, Johnson replied in his typical sarcastic and biting fashion: «This is the proportion. Let me see; forty times forty is sixteen hundred. As three to sixteen hundred, so is the proportion of an Englishman to a Frenchman.»

At that time the English and French could not abide one another. Johnson was no exception to the rule. Ever since the Twelfth Century the two countries had been almost permanently at war. Even today there is still the odd historian or commentator who will refer to the French as «The Old Enemy». (It has to be said that Johnson did not reserve all his bile for the French: he roundly and categorically condemned any person whom he considered to be a foe.)

Johnson’s single-handed A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755, and until the first arrival of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1928, his work was the bible of British orthography.

Samuel Johnson and his equally famous biographer, James Boswell, met in 1763. Johnson was 32 years older than Boswell, a young Scottish aristocrat who was working as a lawyer in London. Despite their difference in age the two men forged a strong and lasting friendship. Boswell admired Johnson with an almost reverential attitude. Some commentators say that, for Boswell, Johnson was a father figure, an older man, kinder and more affectionate than his own father.

When they met, Johnson was living in Gough Square in the City of London, in a house that had been built towards the end of the seventeenth century. The house is open to visitors and is very interesting, especially the top floor where Johnson worked on the dictionary. Here you can leaf through a facsimile edition. It’s worth a look inside the dictionary as Johnson could not resist including his opinions and humorous remarks amongst the entries. The oft quoted example is that of the definition of Oats: «A grain, which in England is generally given. to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.» You can borrow written guides in various languages to the exhibits in the house. Entry: Adults £8, concessions £7, children £4. https://www.drjohnsonshouse.org/

Nearby is Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, a pub in which Johnson used to eat and drink. The local is more or less as it was when it was rebuilt after the Great Fire of London (1666). A notice indicates where Johnson habitually used to sit. You don’t have to pay to go in but perhaps you ought to buy a pint or have a glass of something. The food’s quite good.

A few years after the Great Fire, the architect of the reconstruction of the City, Sir Christopher Wren, had a monument built to the devastation, a column erected at the point where the fire had begun near Pudding Lane. The view from the top, 60 metres above the ground, afforded intrepid citizens impressive views over the rebuilt city. The tower is a mile west of Johnson’s house. Today it is dwarfed by the skyscrapers which surround it although in its time it was a giant on the horizon: it has 311 steps. You’d be ill advised to try to do it without a rest on the way up.

In the 18th century, when most people were quite unaccustomed to heights, the ascent could prove terrifying. One of the people in whom the climb did instil fear was James Boswell. In 1763, the year in which he met Johnson, Boswell decided he should pay a visit to the Monument. Half way up he had a panic attack but he screwed up his courage and carried on to the top as he did not wish to lose face. He described how he felt as he emerged at the top: «…it was horrid to be so monstrous a way up in the air, so far above London and all its spires». If you wish to do the climb you will have to pay: adults £5.80, children £2.90. You can’t buy or reserve tickets on line. You have to queue. But it’s worth it. https://www.themonument.info/

These days the Monument seems tiny in front of the skyscraper, 20 Fenchurch Street, the so-called Walkie-Talkie. Unlike the Monument you can visit this building for free. You only have to reserve on line. Not only do you get a marvellous view of the River Thames and the centre of London from the observation platform, but you can also visit the exotic sky-garden situated on the uppermost three floors of the building. Also up here are bars, restaurants and live music from time to time. https://skygarden.london/

If you fancy the idea of visiting the remaining churches that Wren rebuilt in the decades following the Great Fire, you can choose from the various guided walks offered online. For example, the City Guides website https://www.cityoflondonguides.com/tours offers one of these walks every Tuesday at 11am. It costs £12 and £10 concessions. All these churches would have been brand new buildings in Samuel Johnson’s time and would have been very familiar to him. Those that remain are real gems of seventeenth century London. This walk is highly recommended. City guides offer several other guided walks that explore the neighbourhood in which Johnson lived and worked.

Johnson died in 1784 and you can visit his grave in Westminster Abbey where he is entombed alongside all the other greats of English literature in Poets’ Corner. But, watch out, the admission prices are phenomenal: adults £25, concessions £22, children 6-17 £11, under 6s free. https://www.westminster-abbey.org/