The leyenda negra or the Black Legend is a term invented by Spanish intellectuals in the early 20th century to give a name to what they saw as the continuous anti-Spanish propaganda which, since the conquest of the Americas, had slowly but surely been causing an unwarranted deterioration in the country’s image, and this, in turn, had infected national self-esteem, created doubts that undermined trust in the State and corroded public morale.

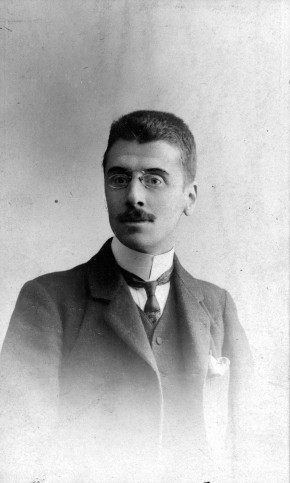

Although the notion of a leyenda negra already existed in the works of several well-known Spanish writers around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the idea was formally formulated in 1913 by Julián Juderías, an official in Spain’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in his prize-winning essay on Spain’s image abroad which was published in the journal, La Ilustración Europea y Americana.

In other words, the original concept of the black legend dates back to a period in Spanish history when Spain had just lost the last vestiges of its great American empire.

Throughout the 19th century Spain was losing its colonial possessions. From Mexico to Chile, the former Spanish colonies rebelled and took their independence. The final blow came in what became known as the Disaster of 1898, when Spain was humiliated in war by the US armed forces, to whom the empire was forced to surrender all remnants of its foreign possessions. Thus it was that the US took control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam. After 500 years, one of the first modern European empires had come to an end. Spain sank into depression and succumbed to a long period of low national esteem. Not only had an empire been lost, but also its reputation had suffered a severe blow..

This is the moment when the idea of the Black Legend was born. It arose as a mechanism to blame all the ills afflicting the country on the malevolent meddling of foreign powers. So it was that an excuse for the loss of Spanish greatness was formulated. Thus, the sense of being defeated was somewhat mitigated. It was more comfortable to consider that a colony had been fooled by an English conspiracy or American propaganda than to think that the people of the colonies really wanted independence from Spain.

In this way, the development of a national inferiority complex was prevented and, over time, the legend came to form a protective psychological shield that deflected further offence to national pride.

From the beginning, the expression has been very well received by historians and the politicians and ideologues of Spanish nationalism and populism; it has always served them as an instrument to combat the introverted tendency of national self-criticism.

The reason the concept went viral overnight is that it became a political tool. ‘The wolf is at the door’ is a simple trick that is as old as the hills, but it is still very effective. If you are a politician or military man and you want the population of a country to stop arguing with each other, to show solidarity and make common cause, one of the tried and tested techniques you can take advantage of is to identify an external enemy, one that would serve to refocus public attention outside the country, blaming rival nations for the particular failure of the moment.

In this case, the creation of the black legend offered the opportunity to lay the blame for the disintegration of the empire on Spain’s European rivals who had painted a false image of a backward, superstitious and violent nation at the head of a destructive empire. It was a conspiracy of hispanophobes, protestants, communists, jews, freemasons and all the liars of Perfidious Albion: all the scum of the earth.

It was they who, over the centuries, had been fomenting discontent throughout the empire, and they who had been stoking the Creole political anger that eventually led to the various uprisings against Spanish sovereignty and culminated in the Disaster of 1898.

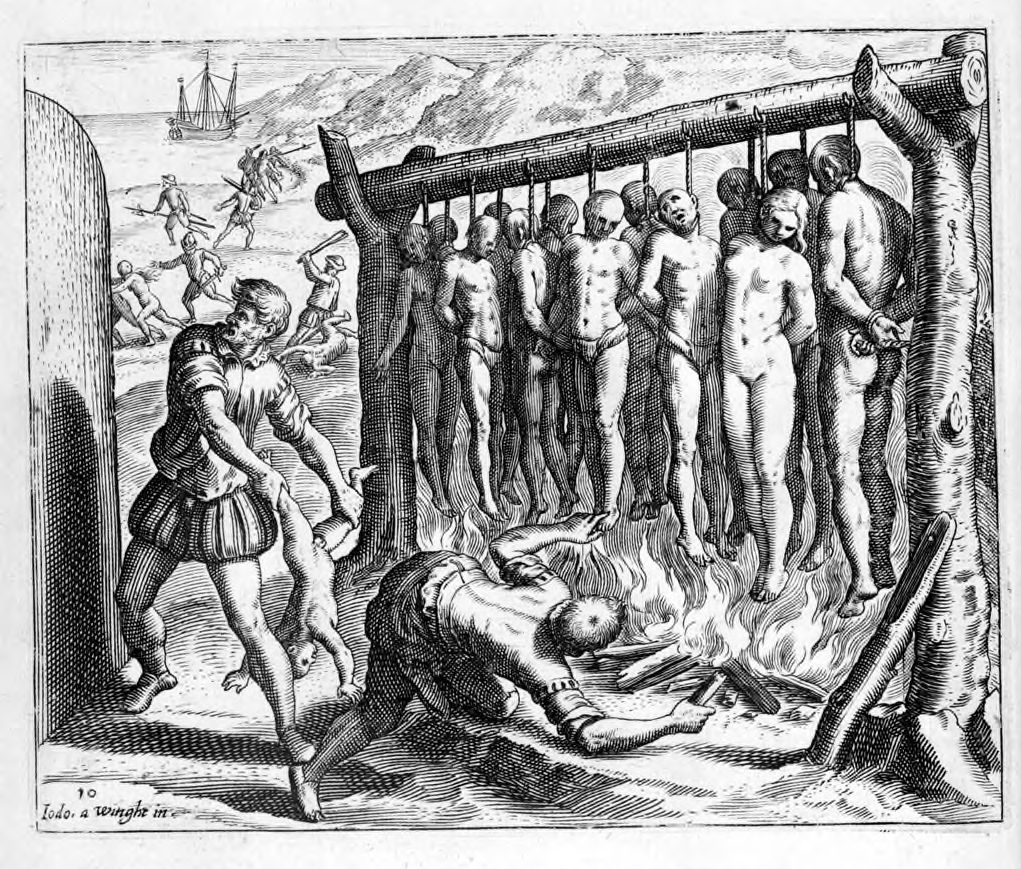

One of the major central themes of the leyenda negra is that Spain’s enemies have been trying for centuries to tarnish the country’s image through negative propaganda that invents, exaggerates and lies about the events that took place in the acquisition of the American colonies. Especially exaggerated are the mortal sins committed by the conquistadors: the atrocities they carried out in order to enrich themselves, the looting and plundering of gold and silver and the crimes they committed against humanity.

Fernando Cervantes, the respected Mexican historian, in his recently published book Conquistadores eloquently details the origins of the legend and argues in favour of it. He asserts that the world of the Conquistadors «was not the cruel, backward, obscurantist and fanatical myth that the legend claims, but the world of the crusades of the late Middle Ages that witnessed the eradication of the last vestiges of Muslim rule in continental Europe».

(Let us overlook the internal contradiction implicit in the sentence in which Cervantes denies that the expulsion of the Muslims was not «cruel, backward, obscurantist and fanatical». Moreover, we will not conclude by extrapolation that «the eradication of the last vestiges of Muslim rule in continental Europe» was any heroic, noble and civilising feat).

There are a number of reasons traditionally adduced to justify or condone the actions of the conquistadors, some of which are echoed by Cervantes.

1 Since the inauguration of the concept of the black legend every enthusiastic supporter of the Spanish empire feels obliged to preface his account of events during the conquest with the observation that we should not judge the behaviour of the conquistadors by today’s standards. They say that the morality of our modern society is new and more sophisticated. They hold that people then did not think the same way as we do today. They were Christians but Christianity was a different thing – no less dedicated to the Lord, but more muscular and visceral. This is also what I was taught at uni, including by Fernando Cervantes himself.

In other words, we have to accept the violence of past centuries, dismiss it as inevitable and say to ourselves, «That was in the past” or «Just close your eyes and ignore it”.

I have never accepted this rationalisation. The conquerors knew what they were doing. They simply chose their own interests over the welfare of the indigenous people.

The crews of the ships that sailed to the Indies were not chosen for their eagerness to preach the gospel. Most of the volunteers who signed up for the adventure of discovering new continents were people who risked everything because they had nothing to lose. Many were poor people, criminals and scoundrels. Many were fleeing from justice. When they signed up for the adventure of discovering the Americas they had been promised gold and the crews of the ships went for it. Of course, the officers in charge of the expeditions were more professional. They had been chosen by the Crown’s agents and represented the king’s interests. So they were in a difficult position; they had to mediate between the conflicting desires of the men on board (to get rich as quickly as possible) and the dictates of the monarch (to find gold and bring it back to the royal coffers as soon as possible, and at the same time to convert the natives to Christianity and make them subjects of the throne).

2 No conquest took place because the tribes did not possess a country to conquer.

3 The so-called conquerors only formed alliances with tribes already disaffected from the other ruling tribes.

4 It was the imported European diseases that decimated the indigenous people. The alleged Spanish violence had little to do with it.

5 Chiefs, commanders and leaders like Cortés did the indigenous people a favour with their annihilation of the Aztecs, an extremely cruel empire with its frequent ritual sacrifices of men, women and children.

It should be added that Cervantes does not defend the cause of the black legend with great conviction. After repeating the obligatory tropes intended to pardon the conquistadors, Cervantes goes on to write the most complete account of the conquistadors’ aggression that I have ever read: the lethal destructuring of the Taino family order, the annihilation of the Aztec army, the razing of the entire city of Tenochtitlan; the many massacres they inflicted all over the continent; the cruelty they handed out to any indigenous tribe that did not wish to accept Christianity, inflicting upon them, torture, slavery and the needless execution of their leaders.

It is a well-written and very detailed chronicle based upon hitherto unexplored primary sources. Indeed, Cervantes has collated many ancient documents. As he says, «From diaries, letters, chronicles, biographies, instructions, histories, epics, encomiums and treatises written by the conquerors, their defenders and detractors, I have tried to weave a story that often reveals surprising and unknown threads.”

There is also another reason commonly used to downplay the seriousness of the behaviour of the conquistadors:

6 There were excesses but the English would have done worse.

For me, this last observation is the most valid of all. The British Empire reigned for a long time over many populous regions of the world and committed countless crimes against humanity. However, to a large extent, we have now come to terms with our violent past and we do not deny the veracity of the crimes our forefathers perpetrated in the name of king and country.

Indeed, several members of the current British royal family accept their country’s responsibility for the empire’s many crimes. For example, next week the king will visit Kenya, the former British colony that gained its independence in 1963 after a decade-long liberation war led by the armed Mau Mau movement. Ten years ago, on the occasion of Kenya’s 50th anniversary of independence, the British government made a historic statement of regret for the «torture and other forms of ill-treatment» perpetrated by the colonial administration during the emergency period and paid compensation of £19.9 million to some 5,200 people.

(Although, it should be noted that, in total, an estimated 90,000 people were executed, tortured or mutilated during the war).

In addition, Prince William said in March 2022, during a speech to the Jamaican Prime Minister and other dignitaries, that «Slavery was abhorrent and should never have happened. I agree wholeheartedly with my father……..who said in Barbados last year that the appalling atrocity of slavery forever stains our history».

So, I ask myself, why can’t so many Spanish historians also accept their nation’s own past crimes, even if they believe that they were committed on a smaller scale? Why do they insist, ad nauseam, that the conquistadors behaved well towards the native peoples during the conquest and that the country’s bad image is only the result of an international conspiracy to tarnish its reputation?

What is remarkable is that all the other European empires of the last 500 years never acquired such notoriety as the Spanish, although they may have have deserved it even more. Significantly, these empires never complained about their own leyenda negra. One is tempted to suspect that the invention of the term became a self-fulfilling prophecy and that Spain’s reputation would have been less tarnished if the authors of the expression had not themselves drawn further attention to the events which occurred during the acquisition of the South American colonies.

However, after more than a century of reification of the black legend, it is too late to cancel or to withdraw the expression. Besides, even the most thoughtful of historians such as Fernando Cervantes still believe in it. Indeed, if you look on YouTube it has some very vociferous defenders. You can watch them now as they rant resentfully against allegations of genocide, fulminate against critics of the Spanish empire and beg you to believe the equanimity with which the conquistadors treated the indigenous peoples with whom they chanced to meet.

As for owning up about the misdeeds of the past, perhaps Spanish regal pride is so strong that no one in the royal family wishes to acknowledge that the «plot» to discredit Spain was nothing more than the reification of a concept adopted by intellectuals in an attempt to preserve the country’s dignity in the face of the defeats of the 19th century.