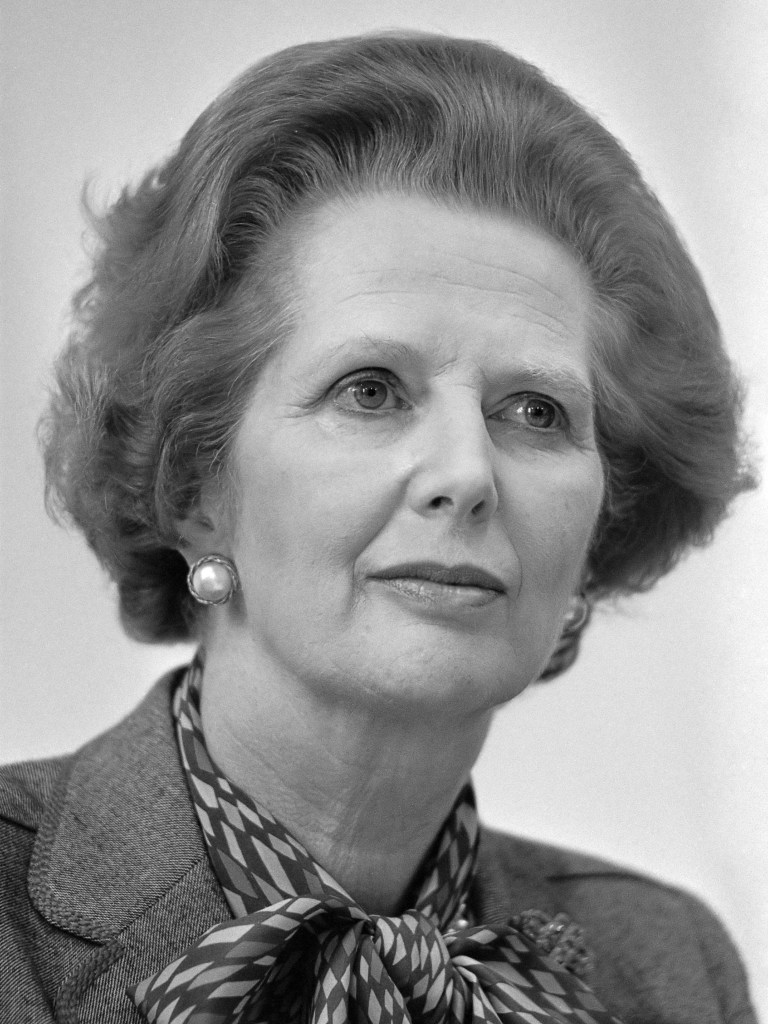

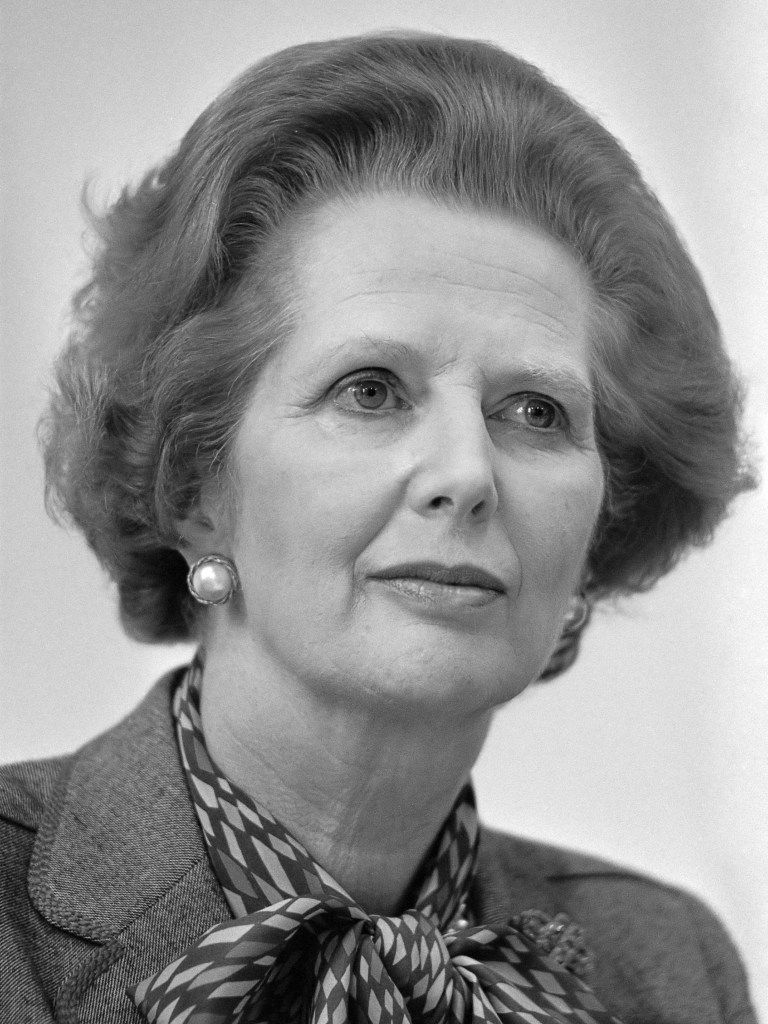

Cómo enfocaba el mundo la señora Thatcher

Recuerdo sentarme en uno de los cubículos de los aseos de la universidad de Sussex en 1972 y ver escrito allí un grafiti que alguien había garabateado justo encima del soporte del rollo del papel higiénico: «Licenciaturas en sociología. Por favor, tome una».

Así, esta persona graciosa, por seguro un estudiante serio de una de las ciencias tradicionales o tal vez un vocero de una de las humanidades de mayor abolengo, mostraba su desdén por esta nueva abominación pseudo académica que algunos progres habían fertilizado en una probeta de laboratorio norteamericano: un feto impío que implantaron en el útero de la madre de asignaturas universitarias para que lo llevaran a término; un resultado de la unión antinatural de la ciencia y las artes; con toda certeza un monstruo bicéfalo enclenque que moriría pronto, siendo biológica e intelectualmente inviable.

¿Un estudio científico de la sociedad? Bah!

Hasta la señora Thatcher, primera ministra entre 1979 -1990) estaba indignada. ¿Sociedad, sociedad? «No hay tal cosa» citaba la revista de mujeres, Woman’s Own, en ocasión de la entrevista que publicaron con ella en 1979.

Al igual que la sociología era una asignatura fraudulenta, el socialismo era una creencia aberrante, ilusoria y mal concebida: un cuento de hadas que procuraba dar derechos a personas que no los merecían. El mito del socialismo tenía que ser desmentido y las estructuras equivocadas erigidas por sus confundidos proponentes deberían ser abolidas.

Ella estaba opuesta doctrinalmente a todas las medidas sociales que se había llevado a cabo anteriormente todo gobierno laborista Hizo misión suya ir cortando por lo sano todo el marco regulatorio que interviniera en la vida del individuo. Creía ella, que si logramos algo en la vida, nuestro éxito se debiera exclusivamente a nuestros esfuerzos personales.

Margaret Thatcher tenía aire de predicadora. Dentro del partido conservador se le consideraba como espíritu renovador: una evangelista e idealista que pregonaba un retorno a valores tradicionales. Proclamaba un mensaje conservador decimonónico. Era resuelta, una fuerza tremenda de la naturaleza. Daba miedo. (Curiosamente, era muy popular entre el público ruso.) Inspiraba a todo gobierno conservador que le siguió a continuar con la tarea principal de privatizar cualquier industria y servicio público que hubiera sido previamente estatalizada por un gobierno laborista.

A ella se debió el resurgimiento del partido conservador de finales del siglo veinte y a ella se debió la ola de desnacionalizaciones que ocurrió a partir de los años 80, la subsiguiente privatización de todos los medios de transporte público y la debilitación y decaimiento del poder de los sindicatos (véase la lucha entre ella y Arthur Scargill el líder del sindicato nacional de mineros). Ella dio rienda suelta a la desestatalización de las utilidades. Los monopolios públicos de luz, gas y agua se hicieron añicos. En su lugar apareció una selva de pequeñas compañías suministradoras.

Estos nuevos pequeños feudos de servicios públicos han hecho retroceder al país a una verdadera economía de libre mercado, suministrando no solo electricidad, gas y agua, sino también caos, ineficiencia y grandes dividendos para sus accionistas: un modelo de capitalismo decimonónico poco adecuado a las necesidades de un economía del siglo 21. Hoy en día, nuestros ríos tienen más mierda que agua…. Ah, y piénsalo bien antes de emprender viaje en el mosaico de las 28 empresas que ahora operan en nuestra red ferroviaria nacional. Los retrasos y las cancelaciones son peores que nunca.

Otra «abominación» que le molestaba a la señora Thatcher era el sistema de viviendas de protección oficial (VPO)

Desde finales de la primera guerra mundial hemos tenido en Gran Bretaña un sistema de VPO construidas por los gobiernos locales. Este sistema tiene sus raíces en la primera guerra mundial. Durante la guerra se observó con alarma el mal estado físico de muchos reclutas urbanos al ejército. El día después del armisticio en noviembre de 1918 el entonces primer ministro David Lloyd George prometió un nuevo programa para mejorar la salud de la población general, un programa que incluía un nuevo sistema de viviendas de protección social. Desde aquella fecha para adelante, cada ayuntamiento en el país tendría la responsabilidad de construir casas dignas de los héroes que habían ganado la guerra. Lloyd George hizo hincapié en que el país tenía una especial deuda de gratitud a los soldados rasos, los miembros de la clase obrera que hicieron que la victoria fuera posible. Alquilarían sus nuevas viviendas a un precio asequible, subvencionado por el Gobierno. Desde entonces las personas que no ganaban el dinero necesario para permitirse el lujo de comprar su propia vivienda podrían vivir en casas de buena calidad y seguridad de tenencia, por cortesía del Estado.

Así fue creado un buen sistema de VPO. Sufrió algunos altibajos debidos a la segunda guerra mundial, pero, hablando por lo general, funcionaba bien y servía bien a la clase obrera británica……

…….. hasta que subió al poder la señora Thatcher que decidió que los inquilinos de las VPO deberían tener el derecho de comprar las casas sociales en que vivían.

Su nueva ley de 1980 mandaba que los ayuntamientos, (Councils), tenían que ofrecer a vender sus casas a cualquier inquilino que ya hubiera vivido en su VPO el período de años necesarios que les diera la elegibilidad de comprar a un precio muy reducido. Aunque habían construido las viviendas con sus propios fondos, los gobiernos locales no tenían permiso de quedarse con el dinero de la venta. Se veían obligados a dárselo todo al gobierno central. Por eso es por lo que todos los ayuntamientos, de cualquier color político, dejaron de construir las famosas «council houses».

La política de Thatcher tenía varios objetivos, principalmente la inclusión de la clase obrera en la democracia propietaria, un término escrito en el corazón del partido conservador. Así el partido pudiera congraciarse con la «alta clase obrera» y darles ánimo a votar conservador.

A largo plazo la intención fue la reducción al mínimo, si no la eliminación entera, del parque de vivienda pública.

A raíz del programa del derecho de compra, el número de estas viviendas ha caído vertiginosamente. Según las propias cifras del gobierno, solo en Inglaterra entre 1980 y 2024 el país perdió alrededor de más de 2,020,279 viviendas de protección oficial.

Esta pérdida ha tenido muy malas consecuencias para los gobiernos locales y ha conducido directamente a llenar los bolsillos de propietarios privados con dinero de las arcas públicas.

¿A quienes pertenecen ahora estas viviendas de protección social?

Como se puede apreciar, una proporción sustancial de los nuevos dueños son las personas a la que la política iba destinada. Pero, en 2013 el periódico The Daily Mirror publicó un análisis de los otros nuevos propietarios que también se habían adueñado de una cantidad importante de las antiguas VPO:

«Un tercio de las viviendas municipales vendidas en los años ochenta bajo el mandato de Margaret Thatcher son ahora propiedad de arrendadores privados. En un borough (distrito) de Londres, casi la mitad de las viviendas de protección oficial están subarrendadas a inquilinos.»

A menudo, estos nuevos propietarios no son individuos sino compañías offshore y las VPOs que poseen forman parte de sus portfolios de inversiones inmobiliarias.

La situación va de mala en peor. Según la New Economics Foundation, para el año 2024 un 41% de las antiguas VPO, previamente la propiedad de los ayuntamientos, estaban siendo alquiladas al precio del mercado, una cifra centenares de veces más alta de lo que pagaban anteriormente los inquilinos del municipio.

¿Cómo se adquieren las ex VPO?

Como en la historia de cualquier casa, llega un momento en que las ex VPO se venden. Los dueños las dejan en herencia cuando mueren. Muchos herederos las venden para dividir las ganancias entre sí. Otras parejas se divorcian y venden la casa. No todos los nuevos compradores quieren seguir viviendo allí felices como perdices para siempre: otros venden porque han comprado su casa a un precio muy razonable del consistorio y quieren sacar provecho realizando un beneficio rápido. Hay tantas otras otras razones por las que las casas se venden.

Pero, sea cual sea el motivo de la venta, el inconveniente es que si eres una de las personas que ha comprado una de estas casas, descubres enseguida que no se venden como churros.

Casas así tienden a atraer hipotecas de mucho menos de 100%. Tienen problemas que no inspiran en los bancos la confianza necesaria para prestar dinero. Hay complicaciones de barrio, de construcción, de reparación, de estar situadas en bloques de apartamentos sociales. En el caso de estos últimos las viviendas comparten tejado o corren el riesgo de revestimiento flamable (como fue el caso de Grenfell Tower en el barrio de North Kensington al oeste de Londres donde en 2017 ocurrió un incendio que se propagó rápidamente, y murieron 72 personas porque no existían ni un procedimiento adecuado para la evacuación ni una vía de escape fácil).

Más aún, la gente corriente a la que se le ocurre comprar un antiguo apartamento municipal son personas que normalmente tendrán menos poder adquisitivo; muchas veces tienen problemas adicionales que les impiden obtener una hipoteca, p ej no tienen el flujo de efectivo para desembolsar entre 1% y 2% del precio de la venta en honorarios a la agente inmobiliario. Además, si no están comprando por primera vez en su vida, se verán obligados a pagar un impuesto (stamp duty) de 5% sobre la banda de precios de viviendas entre £250,000 – £925,000 (la banda típica actual por todo el Reino Unido).

«Lo que necesitas es un comprador rápido»

Un comprador rápido es una empresa (o raras veces un individuo) que tiene el dinero por adelantado para comprar el piso o la casa. Escucha cómo la empresa LDN properties en su web describe su trabajo de comprador rápido. Escucha la canta de sirena, la voz reconfortante de la hada madrina, el rollo del dinero fácil:

«Estas empresas son capaces de hacer ofertas rápidas y competitivas para comprar una amplia gama de pisos y casas en propiedad absoluta o en arrendamiento, independientemente de su forma, antigüedad, estado o tamaño. Se denominan compradores rápidos porque, por lo general, pueden completar el proceso de compra de su vivienda en unas pocas semanas, lo que incluye el intercambio de contratos y todos los demás pasos.»

Son muchos estos conglomerados financieros que no tienen problemas de flujo de efectivo y que disponen de mucho capital al instante. Compran a precios risibles.

«Una clara ventaja de recurrir a un comprador rápido es que no discrimina a la hora de comprar una vivienda y puede considerar casi cualquier tipo de propiedad que podría tener dificultades para venderse con otros métodos, como antiguos pisos municipales, casas heredadas pero no deseadas, propiedades situadas en calles ruidosas, casas de ocupación múltiple, pisos con revestimiento, casas con fosas sépticas, etc.»

Más aún, no se tiene que pagar nada a ningún agente inmobiliario.

Se han producido muchos casos escandalosos que implican a personas en el corazón del partido conservador. Por ejemplo, el magnate Charles Gow y su esposa son propietarios de al menos 40 VPOs de una urbanización del sur de Londres. El padre de Charles Gow fue Ian Gow, uno de los principales ayudantes de Margaret Thatcher y durante los primeros años del derecho a la compra el fue el ministro de vivienda.

No se ha infringido ninguna ley comprando las VPO así. Solo es que el dinero público que se utilizaba para construir esta casa ahora se ha convertido en una mina de oro para un hombre que no la necesita ni para su propia familia ni para su simpática colección personal de gente de barrio.

Las consecuencias para los consistorios y el Ministro de finanzas (y últimamente, el resto de nosotros)

En Gran Bretaña desde 1948 los gobiernos locales han tenido la responsabilidad de ofrecer alojamiento temporal a todas las familias y personas vulnerables sin hogar. La erosión de su propio parque inmobiliario ha hecho que esta tarea sea cada vez más difícil y costosa. Por ejemplo, solo en Londres las 32 boroughs (distritos) de la capital pagan un total de £4m de libras a diario a arrendatarios privados para cumplir con su deber de poner un techo sobre las cabezas de los sin hogar. Irónicamente, para cumplir con su deber, muchas veces los ayuntamientos se ven obligados a alquilar una antigua VPO, una casa de la que eran, en el pasado, los propios dueños, pagando un alquiler a un precio exorbitante. Es decir, no solo las autoridades locales han perdido una vivienda, sino que además tienen que pagar un alquiler inflado a los propietarios privados que ahora son dueños del inmueble. Muchas veces, en el caso de emergencia o de personas vulnerables los nuevos dueños no tienen reparo en cobrar el doble o el triple del precio del mercado.

Además, se han formado asociaciones «especializadas» en alquilar viviendas para gente vulnerable. Por ejemplo, dicen ser especialistas en personas con problemas de salud mental, aunque en realidad no son nada más que empresas privadas que también se ponen las botas, cobrando a los ayuntamientos un alquiler desorbitado. Solo aparentan ser organismos caritativos y responsables. Yo trabajé 40 años en departamentos de servicios sociales ingleses y lo he visto muchas veces.

Cabe mencionar también que el consistorio tiene otra obligación financiera estrechamente relacionada con este debate. Cualquier propietario privado tiene el derecho de alquilar sus viviendas a gente con bajos ingresos; personas que no tienen los fondos necesarios para pagar el dinero que demandan. Si el alquiler no resulta excesivo el consistorio tiene que subvencionar a estos inquilinos pagándoles ayudas (housing benefit).

Conclusión

Claro que hay una constelación de factores que influyen en la escasez de viviendas y el alto coste del alquiler. Los problemas son complejos y confusos pero eso no quiere decir que no tengamos que quedarnos petrificados por miedo o por dificultad. Para resolver cualquier problema complicado tienes que deshacerte de los impedimentos uno por uno, actuando de una manera sistemática. Vamos por partes.

- El derecho de comprar es una variable que sí podríamos eliminar de inmediato. En Escocia ya han dado este primer paso. En 2016 el gobierno autonómico de Escocia derogó la ley por completo y a partir de aquel año el derecho de comprar queda abolido.

- Después podríamos abordar el problema de los pisos de alquiler turístico y las residencias secundarias. Por ejemplo, en el condado de Cornualles, el popular destino turístico al suroeste de Inglaterra, hay pueblos que, en verano, parecen opulentos barrios londinenses, y en invierno quedan vacíos y oscuros. La enorme proliferación de viviendas turísticas y residencias secundarias contrasta fuertemente con la situación de mucha gente autóctona que no pueden permitirse el lujo de tener su propio hogar. Muchos de ellos tienen que subsistir en caravanas y cobertizos. La gente joven no puede independizarse; no tienen la menor posibilidad de competir con la gente adinerada que viene de afuera. El gobierno local (Cornwall County Council) impone un IBI de 200% sobre residencias secundarias y el gobierno nacional impone un impuesto de 5% sobre el precio de compra pero estas medidas fiscales surten poco efecto.

- Podríamos prohibir que los especuladores inmobiliarios dejaran vacíos los edificios y rascacielos que construyen. En el mercado sobrecalentado londinense es suficiente dejar un edificio desierto para que adquiera valor mucho más rápido que la inflación.

- Es Igualmente rentable dejar solares urbanos sin edificar. Si el gobierno quiere que la gente vuelva a vivir en los centros de ciudad debe insistir que cualquier terreno edificable se utilice pronto, y si no, el gobierno debe asegurarse que los ayuntamientos tengan no solo el derecho de adquirir el solar por orden de expropiación forzosa sino también el dinero para emplearlo para la construcción de viviendas a precios asequibles.

- De forma complementaria se debe prestar atención a la expansión urbana incontrolada, la llamada mancha urbana, algo que lleva a la pérdida de hábitat natural. Esta pérdida está exacerbada por la psicología de los ingleses. Todo inglés aspira a vivir en un chalet o, por lo menos, una casa adosada. Por eso es por lo que, entre empresas constructoras y departamentos de planificación, hay una marcada reticencia a fomentar la construcción hacia arriba en lugar de hacia afuera. Ningún gobierno se ha enfrentado al problema de la marea de hormigón de secado rápido que está cubriendo de manera lenta pero segura y para siempre la verde campiña inglesa. El sur de Inglaterra va convirtiéndose en una vasta, ininterrumpida urbanización. En el sureste de este país donde un pueblo termina, otro empieza. Se da la sensación de que estás siempre en las afueras de una ciudad que debe estar ahí, al doblar la esquina. Pero, por cuántas esquinas que dobles, nunca llegas a ninguna auténtica ciudad.

El gobierno acaba de anunciar un programa de construcción de 1,5 millones de viviendas nuevas para el año 2029. Pero, aunque pasaran por alto los serios problemas delineados arriba y se centraran únicamente en números, no van a ser capaz de reducir la escasez así. Ni siquiera disponen de la mano de obra necesaria; desde nuestra salida de la UE no quedan albañiles suficientes en el país.

Nos hace falta un programa completo; un programa que indique un cambio de actitud hacia el problema de la escasez de viviendas. Un programa que sea justo con todos. Tal programa iría en contra de los valores del partido conservador, de su lema, «sálvese quien pueda»; se desataría una tormenta de protestas de la industria inmobiliaria. Y no nos debemos olvidar que el programa implicaría el reverso de la política del derecho de comprar iniciado por Margaret Thatcher.