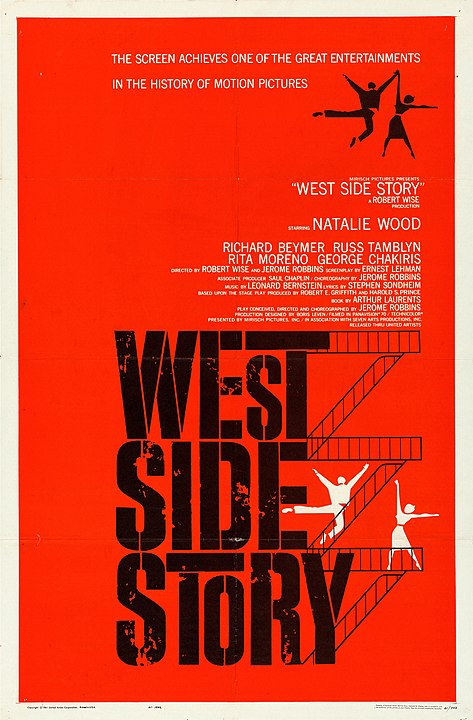

My God, I have read some pretentious opinions about the new West Side Story, none of which have been more pompous than those of the director himself.

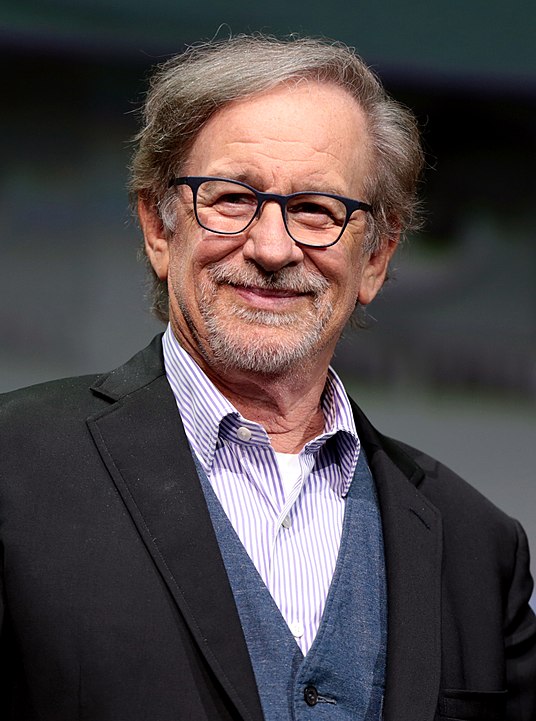

Steven Spielberg tells us that he fell in love with West Side Story at the tender age of 9. Fine, I can’t blame him for that. I, too, by the age of 13, had already seen the film a dozen times. Every week of the summer holidays I would take the bus to the centre of town to hand over my weekly pocket money at the box office of the Curzon cinema. I never tired of the music of Leonard Bernstein and the balletic choreography of Jerome Robbins. The music and the dance thrilled me like nothing else. That’s why I can understand 100% how you can be in love with a film.

Up till that summer I had frequented the Embassy, a flea pit (but cheap) where they used to show old films like Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) with Ginger Rogers and Dick Powell, Road to Morocco (1942) with Bing Crosby, Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour, and Calamity Jane (1953) starring Doris Day. Until one day I got so fed up with all that old-fashioned nonsense, that I walked 200 yards down the road to see what was on at the Curzon.

West Side Story was something else.

Steven Spielberg claims that the object of his new version was to make the story and its characters more true to the 50s in New York, their lives more detailed and believable and their personalities deeper and more rounded. He wanted to make a version that was more acceptable and “less insulting” to a Puerto Rican audience. He added 5% of dialogue exclusively in Puerto Rican Spanish and did not provide subtitles. Just like Abdulrazak Gurnah with the Swahili vocabulary of his novels, Steven Spielberg didn’t want the Spanish translated; he believed that if the whole script had been exclusively in English, this would have impoverished the authentic atmosphere he was trying to create. He sought out young actors of Puerto Rican descent and schooled them in their grandparents’ idioms. He even, in order to protect the sentiments of the Puerto Rican people, censored the lyrics of the famous song “America”, eliminating the couplet in which Anita wishes that the island of her birth should «sink back in the ocean». His West Side Story would be politically correct, a more appropriate parable for our times, a musical against racism and xenophobia.

This is how Steven Spielberg expressed himself, in lofty terms with which no one can disagree and from which no one would wish to dissociate themselves. There is no one today who would dare say no to this goal, because it is all very commendable from a modern perspective that wants to be scrupulously fair to all.

BUT I suspect that Steven Spielberg’s underlying motive has little to do with what he says. What confirms me in this opinion is that he announced before filming that this new West Side Story would be his last film. In other words, to celebrate his retirement, he was going to dedicate his final work to one of his first loves. More than anything else, his swan song is an act of homage and veneration and, at the same time, a sentimental return to his childhood.

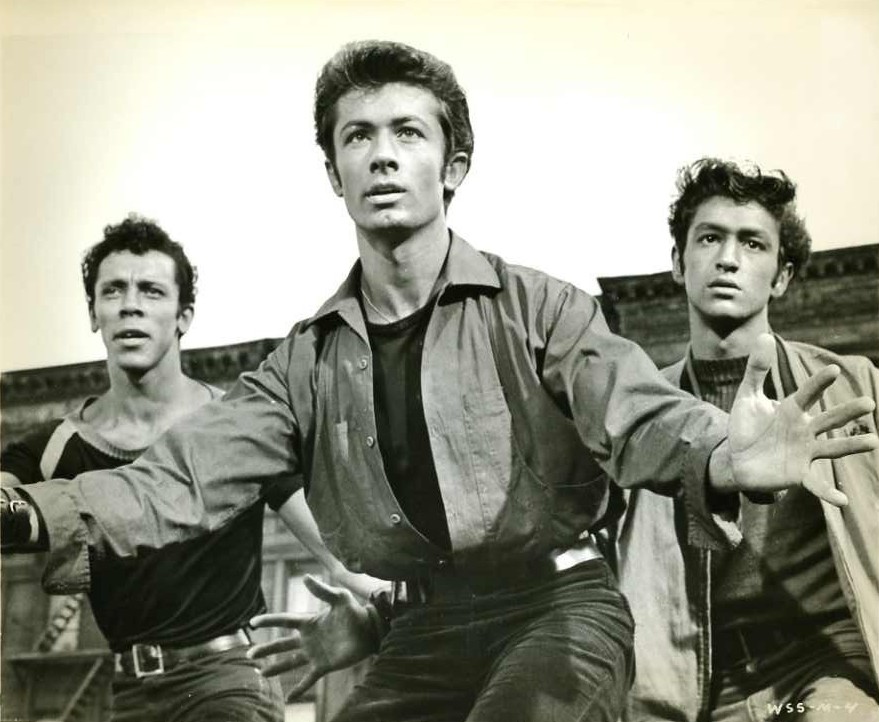

His politically correct motives, his recourse to all the modern clichés about equality, don’t ring true. Since when has it been necessary for a musical to be a faithful representation of reality? Nobody goes to the cinema to see a musical in an attempt to understand delinquency on the streets. It matters little to anybody that the new actor who plays the wife of the leader of the Sharks should be darker skinned than the Anita of the first version. Or that her partner from the first version, George Chakiris, was Greek. And the extra words in Spanish don’t add much.

I may be wrong but it doesn’t seem to me that the new West Side Story has generated any great interest amongst Puerto Ricans. The changes carried out by the new director are irrelevancies to them. If they do feel offended and looked down on, this will have more to do with the unfortunate present reality of the island, caused by the negligent way in which the USA has treated its colony of Puerto Rico throughout the last few years. In 2015 this US territory was obliged to declare itself bankrupt because of the island’s poor administration. In 2017, in the space of one month, the island was battered by 2 hurricanes which caused thousands of deaths and devastated an already weak economy. After the hurricanes came the earthquakes, more than 2000 tremors which claimed more lives, collapsed more buildings and further disrupted the infrastructure.

Despite the fact that the island belongs to one of the World’s most prosperous economies it has yet to recover from the damage inflicted by its recent natural disasters, its poor administration and bankruptcy. It has a National Grid which still has not completely recovered. More than ever, the local people are abandoning their own country to seek their fortune in the States. Today, there are more Puerto Ricans in the USA than on their own island and the words of “America” are more relevant than ever.

Is the American musical an appropriate vehicle for dealing with important matters? I don’t think so. The musical is a frivolous genre, an extravaganza of love, dreams and dance, a journey to wonderland. It is light-hearted fun, a fairy tale, a brightly coloured spectacle full of young, good- looking actors. If this wasn’t the case we would already have had South Atlantic, a clone of South Pacific, only this time set during the Falklands War. Perhaps also, a North Atlantic which tackled the triangular slave trade, a film in which the African slaves dance in leg irons aboard the slave ships. Or Indian Ocean, a musical about the disappearance of the Maldives beneath the waves as a result of the rise in the level of the sea occasioned by global warming. We could have amused ourselves watching the natives dancing on their roofs with the seawater up to their ankles. It would also have been high time for a song and dance western about the genocide of the Native American people.

With this, I return to the starting point. Fundamentally, Steven Spielberg is caught up in the romanticism of a film which he fell in love with 65 years ago. His motivation comes from wanting to be amongst his best friends, having fun with a makeover of one of the loves of his life. And he adores mixing with the survivors of the cast of 1961.

If he had really set out to make entertainment that adds something to the debate about the inherent racism in American society, he might have tried to direct something more like Passing or Queenie and Slim, modern films that not only contain a strong anti-racist message but also a musical soundtrack.

“Steven, you can’t justify your desire to relive your childhood by reciting all the modern clichés about equality. It’s obvious that your yearning to do something politically correct was just a pretext to tinker with a film that many people thought was already perfectly placed in its own time and didn’t need anyone to update it.”

Does it add anything to the original?

Yes. 3 minutes. But the last half an hour seems to go on forever.

PS The idea of modifying the dialogue to allow the actors to express themselves a little more in their own language makes me think of what could be done with William Shakespeare’s original Romeo and Juliet which was first performed in 1597. Perhaps in the future there will be a remake of the stage play in which some director follows Steven Spielberg’s example and for the first time in over 425 years incorporates 5 percent of authentic 16th century Italian dialogue into the script, thus adding a new note of realism to the production.