Gardeners in Great Britain and Ireland maintain that the temperate climate of the British Isles allows them to grow plants from all over the globe. They talk of the benefits of the tropical waters that flow northeast from the Gulf of Mexico and wrap their blessed winter warmth around the fortunate shores of the British Isles, mitigating the effects of the cold that every Winter plunges down from the North Pole.

At this point you have to disregard some parroquial exaggeration. Some coastal areas in the British Isles are often shamelessly described by the domestic travel industry and by tv gardening programmes in Great Britain as “subtropical”. This term tends to cause some derision amongst non-gardeners as well as visitors from abroad. The juxtaposition of the words “subtropical» and “British Isles” tend to conjure up ludicrous images of coconut palms on Brighton beach ( I don’t mean Brooklyn, although that is just as unlikely!) In reality, all the term subtropical signifies here, is that there is less frost in Winter.

However, even this small climatic benefit could disappear. The magazine Nature Geoscience has recently published an article which shows how the Gulf Stream has been weakening for the past two millennia and how this decline has become ever more serious throughout the 20th century: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00699-z. In the future, the Gulf Stream might not arrive at the shores of the British Isles as strongly as before.

Indeed, it may no longer arrive at all. The New York Times points out that another potential setback to the Gulf Stream is the new obstacle in its path: a cold blob of water in the North Atlantic that has arisen just south of Greenland due to the large flow of meltwater flowing south from the North Pole. There is a possibility that this could divert the course of the Gulf Stream away from North-West Europe. (New York Times: In the Atlantic Ocean, Subtle Shifts Hint at Dramatic Dangers. 13/03/2021)

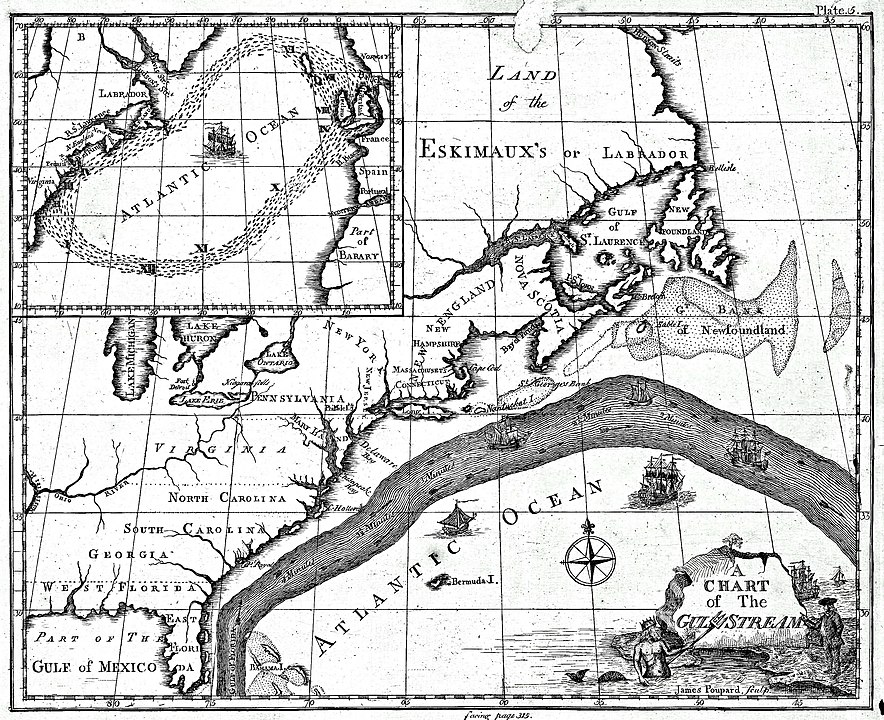

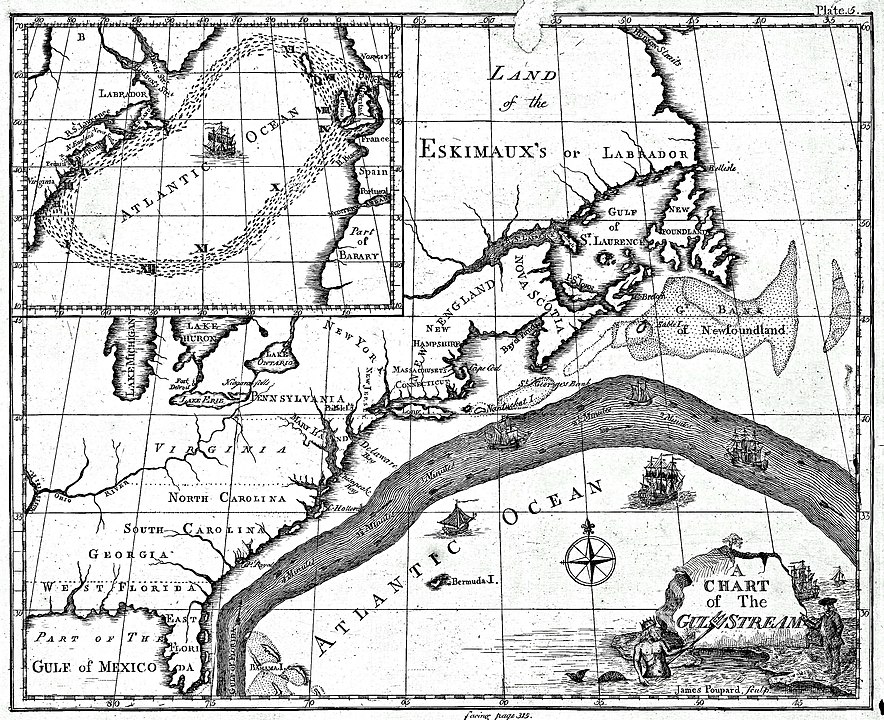

But, all may not be lost. According to Richard Seagar in the American Scientist magazine in 2006 ( The Source of Europe’s Mild Climate ), the idea that it is the Gulf Stream which is mainly responsible for North-West Europe’s mild winters is an outdated and blindly accepted axiom which was made popular by Matthew Fontaine Maury, an American naval officer who in 1855 published The Physical Geography of the Sea, often considered the first textbook of physical oceanography. Maury wasn’t the first to chart the Gulf Stream. Benjamin Franklin did so in 1769, not as an aide to understanding the climatology of Europe but in order to help speed transatlantic mailboats. An article in the New York Times of February 6, 1980, documents the rediscovery of prints of Franklin’s original chart. (“Prints of Franklin’s Gulf Stream Chart found.”)

To challenge the hegemony of Maury’s theory, Seagar pulls together the ideas of several prominent atmosphere modellers, practitioners of a modern discipline which didn’t exist prior to the 1960s, over a hundred years after Maury wrote his pioneering book. Coincidentally, it was exactly the time I was at secondary school and I well remember my old geography master, Mr Plail, alliterating the paramount importance to Britain’s farmers of the “warm, wet, westerly winds in Winter”.

According to these experts (not forgetting Mr Plail), the truth is that this warmth has more to do with the air flow in the northern hemisphere which moves from west to east, spinning south over the Rockies and subsequently veering north-west over the Atlantic, sweeping warm air away from the south-eastern states of the US and delivering it to NW Europe.

In addition, Seagar argues that the major contribution of the sea to Britain’s mild weather is not the effect of the Gulf Stream but the simple absorption by the waters around the islands of the heat of the sun throughout the summer and their gradual release of warmth during the winter. The prevailing south-west wind, the importance of which he has already noted, helps to disperse this warmth over the land.

Seagar says that claims in the press that any change in the course of the Gulf Stream might plunge North-West Europe into a new Ice Age in which its winters come to resemble those of Newfoundland, are alarmist and sensationalist.

The blame, he says, lies with modern-day climate scientists who either continue to promulgate the Gulf Stream climate myth or who decline to clarify the relative roles of atmosphere and ocean in determining European climate. They always fail to mention that the poleward transport of heat by the atmosphere exceeds that by the ocean several-fold.