(A

translation into English can be found below)

Su padre, Antony Gibbs (1756 – 1816), en su carrera inicial, fue

representante de una empresa inglesa que exportaba tejido de lana. En 1778 Antony

volvió a su patria chica, el condado de Devon en Inglaterra donde estableció su

propia fábrica de tejidos. Sin embargo, el negocio fracasó y Antony fue

declarado en quiebra.

En 1789 Antony se decidió a volver a España con el intento de

liquidar sus deudas, restableciéndose como agente de varias empresas

exportadoras británicas. Le acompañaba su mujer. Su hijo, William, nació

en Calle Cantarranas 6, Madrid, el día 22 de Mayo del año 1790. Pero, su madre no

soportaba el calor de los veranos madrileños y en 1792 ella decidió a volver a

Inglaterra, llevando consigo a los 3 hijos, Harriet, Henry y el bebé William.

Los fines del siglo dieciocho y los comienzos del decimonónico fueron

tiempos difíciles para cualquier persona que quisiera establecer y sostener relaciones

comerciales entre Inglaterra y España. Las guerras se sucedieron una tras otra:

la Guerra

anglo-española (1796–1802), otra Guerra anglo-española (1804-1809) y la

Guerra de la independencia española (1808 – 1814).

Fue durante

este período que Antony Gibbs decidió a centrarse en América Latina en busca de

nuevos socios comerciales. Entre los comerciantes británicos de la época esta

estrategia comercial ya se había hecho la sabiduría convencional. Todos se habían

dado cuenta de que los países suramericanos estaban buscando su independencia

de los imperios español y portugués y preferían fortalecerse y aliarse económica

y políticamente por un intercambio de bienes con países europeos prósperos y antagónicos

a España. Los comerciantes británicos reunían ambas características. Para 1808

un 40% de las exportaciones británicas ya estuvo destinado a suramérica.

Antony Gibbs

tenía dos ventajas sobre sus competidores. No solo sabía español sino también

contaba con mucha influencia en el sistema judicial británico: su tío Vicary

Gibbs, era fiscal general y fue por su intervención que Antony pudo obtener

permiso en 1806 por su barco, Hermosa Mexicana, a pasar sin trabas por el

bloqueo naval británico que controlaba las aguas costeras de Francia y España.

Mientras tanto, su hijo, William, asistía al cole en Inglaterra y

dividía su niñez entre Inglaterra y España. De 1806 a 1808 fue aprendiz en

Bristol en la compañia naviera de su tío paternal, George Gibbs, un hombre que

se había hecho rico, entre otras actividades comerciales, en la trata de

esclavos. En 1813, a la edad de 23 años William se hizo socio del negocio de su

padre, trabajando de gestor de la sucursal de Cádiz.

En 1816 su padre murió y William y su hermano Henry se hicieron

con el control de la empresa. La gran idea de importar guano al Reino Unido no se le ocurrió

a William hasta 1840 cuando ya tenía cinquenta años. En sentido estricto la

idea no vino de él sino de su agente en Lima. A principio, le parecía a William

un proyecto descabellado y poco rentable. Pero, antes de que el pudiese decir

que no, el agente había firmado un acuerdo para comprar el guano del gobierno

peruano. Por suerte, William había subestimado la manía victoriana por la

jardinería. El guano se vendía como pan caliente, por decirlo así.

Obtuvo el

guano de las islas Chincha, situadas frente a la costa peruana. En aquél

entonces estaban cubiertas de una capa de treinta metros de profundidad de

excrementos de aves marinas, en su mayoría los de los pájaros bobos, los

llamados alcatrazes piqueros. Había millones de toneladas listas para

llevárselas.

En

cantidades limitadas el guano, lleno de nitratos, fosfatos y potasios es un fertilizante

ideal. Pero, su enorme concentración en las islas Chincha las convertía en áridos

y cáusticos entornos muy dañinos a la salud de cualquier ser humano expuesto a ellos

a lo largo de un período prolongado. Nada florecía en condiciones tan ácidas y

hostiles, mucho menos los hombres que fueron mandados a la fuerza a trabajar

allí.

A principio, las excavaciones fueron llevadas a cabo mayormente

por presidiarios, desertores del ejército peruano recapturados y esclavos. De

esta manera el gobierno peruano mantuvo el coste de producción a un nivel mínimo

e hizo que la extracción fuera lo mas rentable posible.

En 1849, cuando se necesitaban mas trabajadores forzados se

empezaba a introducir mano de obra china “contratada”, este término siendo un

eufemismo para la esclavitud. Estos peones eran secuestrados o engañados y luego

detenidos en barracones antes de ser transportados al Peru.

En el siglo decimonónico las estimaciones de la tasa de mortalidad entre los chinos raptados varían de investigador a investigador. Algunos estimaron que entre 1847 y 1859 murieron un 40 por ciento de estos culis (coolies en inglés) durante la singladura a las islas Chincha. Otros dijeron que más de dos tercios de los sobrevivientes fallecieron durante su período de “contratación”, la duración de un “contrato” siendo típicamente de unos 5 o 7 años. Además, si duraron al final del “contrato” los chinos se vieron forzados a continuar a trabajar hasta que cayeron muertos. En 1860 se calculó que no sobrevivió ni un solo chino de los 4,000 transportados a las islas desde el comienzo de la industria. Si solo un 50 por ciento de estas afirmaciones fuera verdad las islas tendrían menos de esclavitud y más de campos de concentración nazis.

Lo que no está en duda es la índole del régimen de brutalidad con

el que los peruanos gobernaban a los trabajadores. Todos los testigos – y hubo

muchos – atestaban que la disciplina consistía de flagelaciones y torturas. A unos 25 kilometros de la costa, era

imposible que los esclavos escaparan nadando. El único método de evasión

infalible fue el del suicidio. Según el Journal of Latin American Studies

un marinero norteamericano alegó que hubo un caso en 1853 en el que 50 chinos

se cogieron de la mano y se lanzaron de un precipicio a su muerte en el mar.

Todas las tripulaciones de las docenas de barcos que acudían a las

islas para llenar sus bodegas con los sacos llenos de guano comentaban sobre la

barbaridad de las condiciones y habría sido imposible que ningún comerciante de

guano no hubiera sido consciente de las condiciones infrahumanas que existían

en las islas.

Con la fortuna que ganó con la venta del guano William Gibbs hizo

construir en un valle pintoresco de la campiña inglesa, a unos kilómetros al

oeste de Bristol, la enorme mansión de lujo, Tyntesfield.

Es la casa emblemática del estilo gótico victoriano. El arquitecto

Marc Girouard ha dicho de la casa que, “Estoy seguro de que ya no hay otra casa señorial victoriana

que represente tan suntuosamente su época que la de Tyntesfield”.

Durante la segunda mitad del siglo veinte la condición de la casa

se deterioró hasta que las reparaciones que hacían falta hubieran costado otro

dineral. La familia nunca se las llevaron a cabo. El último habitante de la

casa, Richard Gibbs, un soltero que vivía solo y en sus últimos anos únicamente

ocupaba tres de las habitaciones mas pequeñas, decidió que la casa debiera ser

puesta en venta a su muerte.

En 2002 la casa fue comprada por The National Trust, una sociedad

benéfica dedicada a la conservación del patrimonio nacional de Inglaterra,

Gales, e Irlanda del Norte.

Es aquí donde se sitúa este otoño la exposición, “William Gibbs, From Madrid to Tyntesfield”, una muestra subtitulada, “A story of love, loss and legacy,” un cuento de amor, pérdidas y herencias. Muchos de los objetos expuestos son obras de arte coleccionadas por William Gibb en España y América Latina. Son en su mayoría cuadros religiosos, entre los cuales destacan varios: el de San Lorenzo llevando la parrilla en la que los romanos le quemaron vivo (William compró este cuadro creyéndolo una obra de Zurbarán aunque hoy en día está atribuido a su contemporáneo, Juan Luís Zambrano de Córdoba; la Inmaculada Concepción de Alonso Miguel de Tovar, una copia del cuadro de Murillo que hoy se expone en el Prado; hay también uno de Murillo si mismo, uno de sus varios Mater Dolorosa. Sin embargo, la más impresionante de todas las obras exhibidas es la exquisita Madonna col bambino e Giovanni Batista de Giovanni Bellini pintada alrededor del año 1490. La exposición también incluye muebles, libros, retratos de la familia y otros dispositivos misceláneos. De estos últimos cabe destacar un par de pequeños sahumadores peruanos en forma de pavos reales hechos de filamentos dorados y utilizados como incensarios por los Gibb, una familia anglo-católica. (En la cornisa de madera en la biblioteca está grabado en castellano, “En Dios mi amparo y esperanza”, el lema personal de William Gibbs.)

En paralelo

con esta exposición, Tyntesfield pone otra pequeña muestra fotográfica en la que

se contrastan la aridez, esterilidad y desolación de las islas Chincha con la

opulencia de la casa y la lujuria de los jardines que la rodea. Esta pequeña

exposición adicional durará hasta el 4 de noviembre.

Cosa interesante: cerca de la despensa del mayordomo en la planta

baja de la casa hay un vitral, una ventana en la que el vidrio contiene hileras

de imágenes, alineadas al tresbolillo, de los alcatraces, los pájaros que

hicieron la casa posible. (No se ven conmemorados los chinos.)

Además de los jardines ornamentales, la casa posee un huerto

amurallado en que se cultivaban las frutas y hortalizas para el consumo de la

familia. Al lado hay varios invernaderos, uno de ellos una orangery, una

estufa especial, diseñada para el cultivo de naranjos (cosa nada fácil en el

clima inglés).

La capilla es inmensa y da la impresión de un mini-catedral. Está

modelada en la Sainte Chapelle, el templo gótico situado en la Íle de la Cité

en Paris. El trabajo es impecable.

Como ya se ha notado, William Gibbs fue un anglo-católico devoto y

después de que se jubilara dió enormes cantidades de dinero para la construcción

de iglesias, capillas y otros edificios asociados con su fe, los más famosos

siendo la capilla y el gran salón de Keble College, Oxford.

La casa está abierta todos los días menos el día de Navidad y la

exposición durará hasta el mes de diciembre. El horario de Tyntesfield y el

precio de las entradas se ven en la web del National Trust.

The exhibition, “William

Gibbs, From Madrid to Tyntesfield.”

His father, Antony Gibbs (1756 – 1816), in his early career, was an

agent for an English exporter of woollen cloth. In 1778 Antony returned to his childhood

home, the County of Devon in England, where he started his own cloth-making

factory. However, the business failed and Antony was declared bankrupt.

In 1789 Antony decided to return to Spain with the intention of

paying off his debts. Once again he acted as an agent for several British

exporters. He was accompanied by his wife. His son, William, was born at 6

Calle Cantarranas, Madrid, on 22 May 1790. However, his mother was unable to

bear the heat of the Madrid summer and in 1792 she decided to return to

England, taking with her the 3 children, Harriet, Henry and the baby William.

The end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th

centuries were difficult times for anybody seeking to establish and sustain

business links between England and Spain. Wars came one after another: The

Anglo-Spanish War of 1796 – 1802, another Anglo-Spanish war 1804-1809 and the

Peninsular War of 1808-1814).

It was during this period that Antony Gibbs decided to look

towards Latin America in his search for new business partners. Amongst British

merchants this commercial strategy had already become the conventional wisdom

of the age. They had all realised that South American countries were seeking

independence from the Spanish and Portuguese empires and preferred to strengthen

their position by seeking to ally themselves economically and politically

through an exchange of goods with prosperous European countries that were

thriving and antagonistic to Spain. British firms fulfilled both of these

characteristics. By 1808 40% of all British exports were destined for South

America.

Antony Gibbs had two advantages over his competitors. Not only

could he speak Spanish but he could also rely upon the great influence he

enjoyed in the British judicial system: his uncle, Vicary Gibbs, was Solicitor

General and it was through his intervention that Antony was able to obtain

permission in 1806 for his boat, Hermosa Mexicana, to pass without hindrance

through the British blockade that controlled the seas around the coasts of

France and Spain.

Meanwhile, his son William was going to school in England and dividing

his childhood between England and Spain. From 1806 to 1808 he was apprenticed

to the shipping firm belonging to his paternal uncle, George Gibbs a man who

had made himself rich, amongst other commercial activities, through the slave

trade. In 1813 at the age of 23 William was made a partner in his father’s

firm, managing the Cadiz branch.

When his father died In 1816 William and his brother Henry assumed

control of the business. However, the great idea of importing guano into the

United Kingdom didn’t occur to William until 1840 by which time he was already

fifty years old. Strictly speaking, the idea didn’t come from William but from

his agent in Lima. In the beginning the project seemed hare-brained and

unprofitable. But, before he could say no, his agent had signed an agreement

with the Peruvian government to buy the guano. Luckily, William had

underestimated the Victorian mania for gardening and the guano sold like hot

cakes, for want of a better expression.

He obtained the guano from the Chincha Islands, situated off

the Peruvian coast. At that time they were covered in a layer of seabird

droppings some thirty metres thick, mainly the excrement of Boobies, the

so-called blue-footed albatross. There were millions of tons ready to go.

In limited quantities, the guano, full of nitrates, phosphates and

potassium is an ideal fertiliser. But its enormous concentration on the Chincha

Islands made them an arid and caustic environment, very harmful to the health

of any human being exposed to it for a prolonged period. Nothing flourished in

such hostile and acid conditions, least of all the men who were forced to work

there.

At the beginning the digging was mainly done by prisoners, recaptured deserters from the Peruvian army and slaves. In this way the Peruvian government kept the cost of production to a minimum and made the venture as profitable as possible.

In 1849 when more forced workers were needed, they began to import

“indentured” Chinese labourers, this term being a euphemism for slavery. These

labourers were kidnapped or duped and held in barracks until they were

transported to Peru.

In the 19th century estimates of the mortality rate of these Chinese forced labourers varied from investigator to investigator. Some estimated that between 1847 and 1859 40% of these coolies died on the journey to the islands. Others said that two thirds of the survivors died during their “indenture”, the duration of said “indenture” lasting 5 or 7 years. Moreover, if they lasted to the end of the “contract” the Chinese were forced to continue working until they dropped dead. In 1860 it was calculated that not one of the 4,000 Chinese who had been transported to the islands since the beginning of the industry had survived. If only 50% of these claims were true the islands would have been more like Nazi concentration camps and less like slavery.

What is not in doubt in the nature of the brutality of the regime

with which the Peruvians governed the workers. All the witnesses — and there

were many — attested that discipline consisted of whipping and torture. At a

distance of 25 kilometres from the coast it was impossible for the workers to

escape by swimming. The only infallible escape was suicide. According to the

Journal of Latin American Studies an American sailor alleged that there was a

case in 1853 in which 50 Chinese linked hands and jumped from a precipice to

their death in the sea.

All the crews of the dozens of boats that came to fill their holds

with the sacks of guano commented on the barbarity of the conditions and it

would have been impossible for any dealer in guano not to be aware of the

subhuman conditions that obtained in the islands.

With the fortune he made from the sale of the guano William Gibbs

built, in a beautiful valley in the British countryside, a few kilometres to

the west of Bristol, an enormous luxury mansion called Tyntesfield. It is the

archetypal Victorian gothic mansion. The architect Marc Girouard has said of

the house, “ I feel quite confident in saying that there is now no other

Victorian country house which so richly represents its age as Tyntesfield.”

During the

second half of the 20th century the house became dilapidated to the

extent that the necessary repairs would have cost another fortune. The family

never carried them out. The last inhabitant of the house, Richard Gibbs, a

bachelor who lived alone, and in his final years only occupied 3 of the smaller

rooms, decided that the house ought to be put up for sale upon his demise.

In 2002 the

house was bought by The National Trust, a charitable society dedicated to the conservation

of sites of national heritage of England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

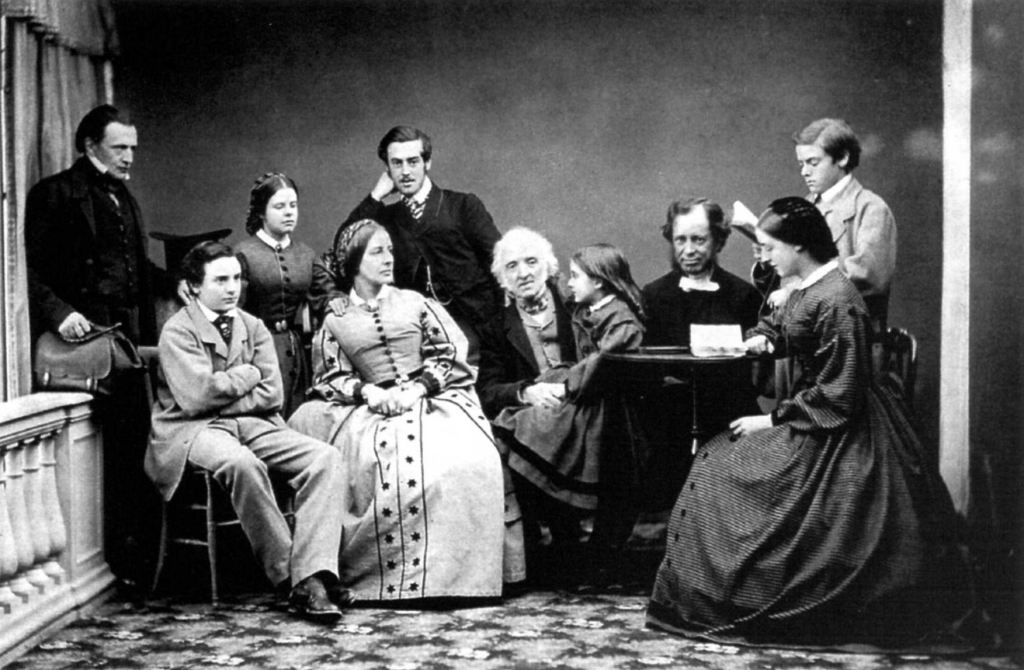

It is here, this autumn, that The National Trust is showing, “William Gibbs, from Madrid to Tyntesfield”, an exhibition subtitled, “A story of love, loss and legacy”. Many of the objects on show are works of art collected by William Gibbs. They are in the main religious paintings, amongst which the most outstanding are: Saint Lawrence carrying the grid iron upon which he was to be roasted to death (William bought this painting believing it to be by Zurbarán, although nowadays it is attributed to his contemporary, Juan Luís Zambrano of Córdoba; the Inmaculada Concepción of Alonso Miguel de Tovar, a copy of the painting by Murillo that today is on show in the Prado; there is also one by Murillo himself, one of his several Mater Dolorosa. However, of all the works exhibited is the exquisite Madonna col bambino e Giovanni Batista by Giovanni Bellini, painted around the year 1490. The exhibition also includes items of furniture, books, portraits of the family and other miscellaneous devices. Outstanding amongst the latter are a pair of small Peruvian perfume burners in the form of peacocks fashioned from gold filament and used as censers by the Gibbs, an anglo-catholic family. (Engraved in Spanish on the wooden cornice in the library is the personal motto of William Gibbs, “En Dios mi amparo y esperanza”, “In God my Refuge and Hope”.)

Running in

parallel with this exhibition Tyntesfield is also showing another small

exhibition of photographs which contrast the aridity, sterility and desolation

of the Chincha islands with the opulence of the house and the lushness of the

surrounding gardens. This additional exhibition runs until 4th November.

An interesting note: near the Butler’s pantry on the ground floor

there is a stained-glass window which contains images, arranged in staggered

lines, of the albatrosses which made the house possible. (There is no homage to

the Chinese.)

Besides the ornamental gardens, the house possesses a walled

garden in which were grown the fruit and vegetables for the consumption of the

family and staff. By the side of this there are several greenhouses, one of

them an orangery, a hothouse specially designed for the cultivation of oranges

(not an easy thing in the English climate.)

The chapel is immense and gives the impression of a

mini-cathedral. It is modelled on the Saint Chapelle, the gothic temple

situated on the Íle de la Cité in Paris. The building is impeccable.

As we have already seen, William Gibbs was a devout Anglo-catholic and after he retired he paid enormous amounts of money for the construction of churches, chapels and other buildings associated with his faith, the most famous of these being the chapel and Great Hall of Keble College, Oxford.

The house is open every day except Christmas Day and the

exhibition will run until December. The opening hours for Tyntesfield and the

price of admission can be found on the web page of The National Trust.